I was walking down Bill Lee’s driveway at Laughing Valley Ranch in Clear Creek County when he said he wanted me to try something.

We’d been spending the last few hours brushing, saddling and walking two of Lee’s burros, Jack and Mr. Ziffel, up and down his property high above Idaho Springs.

Halfway down the hill on the way back to his house, he tells me to bring the rope I’ve been using to guide the 30-year-old, 500-pound Mr. Ziffel behind the animal’s keister.

“Get ready to run fast,” he says. “And try to hold on.”

A moment later, Lee yells “hee-ya!”

Before I knew it, I was getting yanked forward at an unmatchable pace by an open-throttled donkey. The speed, power and control of Mr. Ziffel galloping next to my thrashing limbs was impressive and intimidating. I dropped the rope to keep from tumbling down the hillside, and Mr. Ziffel sped away without a care in the world.

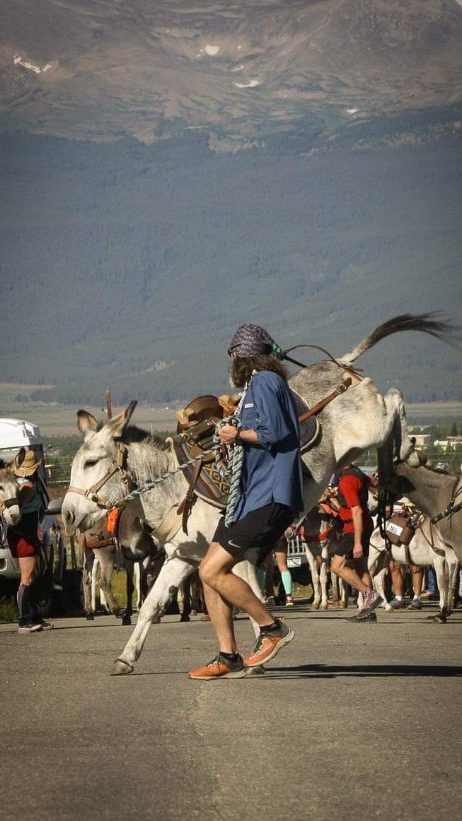

This was my first glimpse into the art of pack burro racing, an extreme sport that involves running alongside your hairy and hooved teammate in a mashup of historic mining tradition, fearless endurance running and skilled equine care and handling.

After 75 years of official races, the sport is seeing an uptick in popularity as new events spring up around the Mountain West and established races gain more participants and thousands of attendees.

Lee, who is somewhat of a legend in the sport and still racing at 75 years old, is preparing me for the eight-mile, “beginner friendly” burro race in Georgetown the following day.

I’m just hoping to keep up.

The way of the burro

The first thing a veteran burro racer will tell you is that it’s a donkey’s race.

“If anybody tells you it’s not 80% donkey, they’re lying to you,” says Tracy Loughlin, who has won the women’s division Triple Crown the last two years.

The fastest runners in burro races aren’t always the most competitive. What matters is the relationship between teammates — a bond that takes time and commitment.

WHAT IS A BURRO?

Burro is Spanish for donkey, and they were first introduced to the Southwest by Spaniards in the 1500s. You can spot them by their trademark long ears and short mane. They can be a variety of colors, like brown, gray or white, reaching heights between 2.5 to 5 feet at the shoulder. Some of the taller burros are the size of horses.

“It’s truly a partnership,” says Loughlin, who’s been running with a donkey named Mary Margaret for 12 years. “I can see when her ears go, what she’s gonna do. I can tell if she’s going to jump over a rock or she’s going to take a wide turn because she sees something in the bushes. And if you can’t anticipate those things … you’ll get passed in a race.”

But it’s not always that easy. Donkeys can rear, kick and even run loose off the track altogether. Sometimes donkeys lose motivation mid-race and won’t budge. The beginning can be particularly chaotic because they all take off together in a herd after the starting gun.

“I think people who’ve never been to a burro race sometimes come and think they’re cute, petting zoo donkeys. These are athletes,” says Loughlin. “We’ve trained these donkeys to run really fast and it can be dangerous. They don’t stand around all calm just waiting for the gun to go off. They know this is a race.”

Another part of the challenge is figuring out a donkey’s strengths, weaknesses and quirks. Most burros don’t like shadows. Some don’t like bushes — others like eating them. Mary Margaret has sensitive feet.

Once runners begin to understand what makes their partner tick, then they’re really ready to haul ass.

“There’s no relationship or bond like it,” Loughlin says. “It’s super cool to learn her and figure her out, and I’m still figuring her out. I still don’t know her exactly, but then to put her in a race and see it all come together is super fun.”

‘Bringing history alive’

People have bonded with donkeys long before the first burro race. These critters were integral in helping miners carry loads of equipment and ore up and down mountains in the early days of the Centennial State. The development of familiar mountain towns, and greater Colorado, followed.

“Burros are special animals — this state was built on the backs of burros,” says Bill Lee, who is referred to as a godfather of the sport and teaches the history of Colorado’s frontier days by dressing up as a character known as Red Tail the Mountain Man at town festivals.

When mining prospects dwindled, Lee says burro racing breathed new life into struggling mountain towns, and in essence saved them by drawing racers and watchers alike. It’s not exactly clear how it first started, but legend has it that two miners raced into town to claim gold they found at the same location. Because the burros were loaded down with supplies, the miners ran alongside them.

That history is still acknowledged in today’s races. For example, donkeys are required to carry a few essential miner tools: a pickaxe, a shovel and a gold pan.

“We’re bringing history alive,” says Lee. “We’re bringing traditions back.”

Donkey dynamics

People who interact with them find favorites and quickly become attached to these humble animals. In Georgetown, one woman approached Mr. Ziffel with homemade treats she knew he liked, saying he was her “first donkey love.”

Those emotions extend to the racers. Bob Sweeney, a leader in the sport, describes the feeling of euphoria he experiences running next to Yukon.

“There’ll be no tension on the rope at all and we’ll just be running stride for stride together,” he says. “You’re both running at a speed where you both feel good, and everything is in sync. There’s just something magical about that.”

Lee wants to give domestic livestock “purposeful and productive lives.” He raises all kinds of animals, from donkeys and horses to reindeer and alpacas, and brings them to schools, pageants and senior centers. Although he’s lost a step since his ultra-marathon days, racing burros gives him a purpose, too.

“It’s like doing 100-milers — it’s just a challenge,” he says. “Why did a blind man climb Mount Everest? Because the challenge of being the first blind man to ever do it. This is part of the challenges people take on to make life a little fuller.”

There are whole mountain festivals that rally communities around donkeys, like Fairplay’s annual Burro Days. The weekend-long affair has gold panning, Cowboy Church, a parade and more, but one of the premier attractions is the World Championship Pack Burro Race that takes burro-runner teams on a 29-mile out-and-back race to the top of Mosquito Pass (13,185 feet).

Like with other donkey-centric events across the state, it’s a celebration of both the community and the burro’s role in the town’s past.

“Burro racing, surrounded by the Burro Days event, is instrumental in our community for keeping that history alive,” says Julie Bullock, events coordinator for the Town of Fairplay. “And also for bringing economic development into our area.”

Last ass

Credit: Jay Holland

For Steve Indrehus, an organizer of the Georgetown race, it’s less about winning races than it is about having a good day running with burros in the mountains. As the sport gets more popular, he hopes people remember that “it’s all about the ass.”

“I could go do one of these runs any day of the week without a burro, and I’d be bored pretty dang quick,” he says. “But put a burro in my hand — it makes the run interesting.”

Marching alongside Mr. Ziffel had a similar effect. I spent most of the Georgetown race jostling with him for position, keeping him close and staying ahead on downhills to not repeat what happened going down Lee’s driveway the day before. While having a 500-pound animal snort on your calves halfway up a mountain is a surreal experience, by the end of the race it felt like there was at least some level of mutual understanding between us.

As we crossed the finish line after nearly two hours on trail, I got a glimpse into the camaraderie and connection that attracts people to the sport.

The Georgetown event has come and gone, but the burro racing season is only just beginning. The biggest competitions of the summer, those that make up the Triple Crown (Fairplay, Leadville and Buena Vista), are all smashed into three consecutive weekends starting July 28. Other events are sprinkled throughout the upcoming months until mid-September.

Pack burro races to check out this summer

Creede’s Burro Race: The Donkey Dash.

10 a.m. Saturday, June 8, Creede

Greenland Pack Burro Race.

10 a.m. Sunday, July 14, Larkspur

World Championship Pack Burro Race.

10:15 a.m. Sunday, July 28, Fairplay. First leg of the Triple Crown series.

“If you finish that race the sun’s still up, you did pretty darn good.” – Tracy Loughlin

Leadville Pack Burro Race.

10 a.m. Sunday, Aug. 4, Leadville. Second leg of the Triple Crown series

Buena Vista Pack Burro Race.

10 a.m. Sunday, Aug. 11, Buena Vista. Third leg of the Triple Crown series

South Fork Pack Burro Race.

10 a.m. Saturday, Aug. 31, South Fork

Victor Pack Burro Race.

Noon. Saturday, Sept. 7, Victor

Frederick Pack Burro Race.

10:30 a.m. Saturday, Sept. 21, Frederick

Loughlin says she wouldn’t be competitive running on her own against other participants who are faster than her, but “the donkey is the great equalizer.” Even though burro race winners are sometimes separated by gender divisions, like in the Triple Crown, her eyes are set on winning each competition this summer outright.

“My goal is to beat the men,” she says. “My goal is to show little girls that women can do everything that a man could do, especially in a sport like this where you don’t have to segregate the genders. So that’s, to me, the coolest part about the sport.”

After finishing as the overall winner of the Georgetown race, Loughlin is well on track to achieve that goal.

Although he has some wins under his belt, Lee hasn’t always finished on the podium over the last four decades raising, handling and running burros. More importantly, he says he continues to learn important life lessons from them.

“We learn from our mistakes, we learn from the past, we learn from history,” he says. “Life will not be easy. And even if you just lead a normal life, it won’t always be easy. You have to face life’s challenges … and you learn to adapt.”