“Under Colorado law, I cannot sell you psilocybin,” an employee tells the crowd gathered at the Mad Hatter booth. “If you buy a sticker, I can gift you some product. We have candy, capsules and dry,” the latter referring to the actual mushrooms that potential customers have come here to procure.

The vendor is walking the fine line created by Proposition 122, which last year decriminalized so-called magic mushrooms and other psychedelic drugs in Colorado but did not legalize them for sale. Adults over the age of 21, however, can give them as gifts to other adults.

That’s why the 20 businesses at Denver’s inaugural ShroomFest, held June 9 at event venue ReelWorks, are hawking t-shirts, consulting sessions and tote bags with drugs on the side for free. Some 1,200 people paid $65 apiece to attend, presumably if not technically for the chance to get their hands on shrooms, infused chocolate bars and psilocybin-packed pills. Spores, liquid cultures and grow kits were also popular offerings.

'Research purposes'

Spores are another loophole. Until they have been germinated, they don’t contain the compound that makes mushrooms psychedelic, so they’re technically legal. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) put out a statement earlier this year clarifying that spores are legal under federal law.

“If the mushroom spores (or any other material) do not contain psilocybin or psilocin (or any other controlled substance or listed chemical), the material is considered not controlled under the [Controlled Substances Act],” the statement read. “However, if at any time the material contains a controlled substance such as psilocybin or psilocin (for example, upon germination), the material would be considered a controlled substance under the CSA.”

Nearly every vendor at ShroomFest were themselves customers of Altitude Consulting or other labs that test for potency and make sure products like spores and cultures don’t contain too much psilocybin.

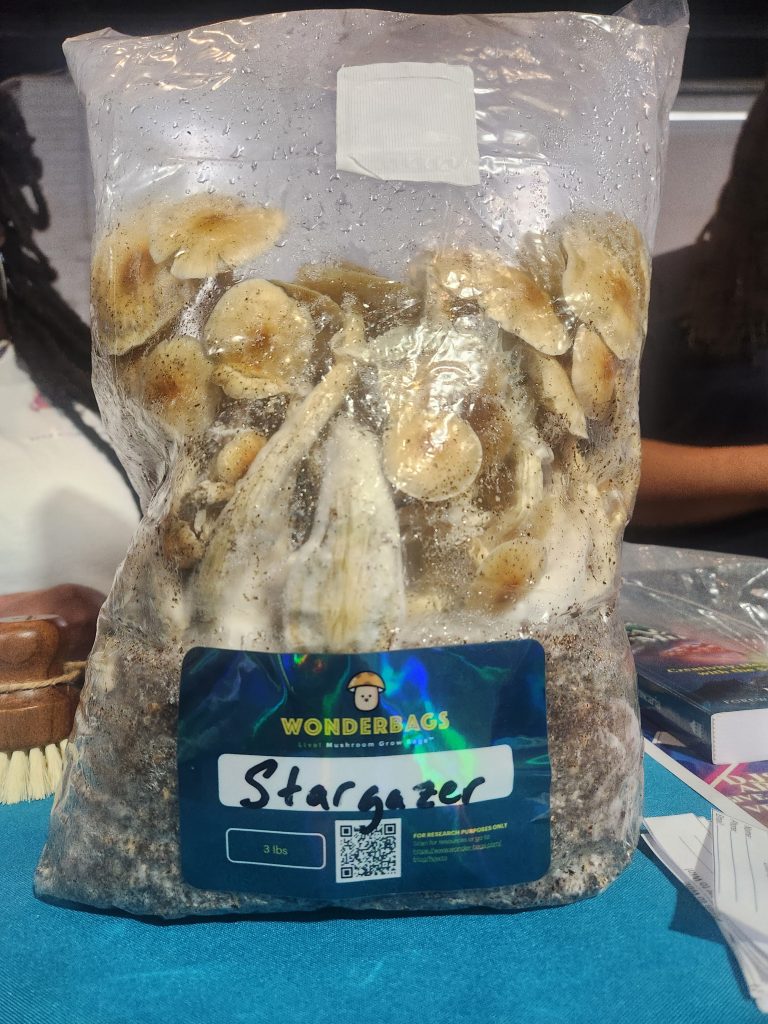

Assuming their products pass the lab test, businesses also have to be careful in their advertising and marketing. It is still federally illegal to sell products intended for consumption that have the potential to develop into psychedelics (like spores), so companies like Wonderbags, based in Colorado Springs, label their live mushroom grow kits with the disclaimer, “For research purposes only,” before shipping them throughout the U.S.

Phil Foote, Wonderbags’ market manager, rattled off a dozen states the company ships to — and the ones they don’t, including California, Idaho and Georgia, which prohibit spores.

“Making sure everything is legal,” is the top concern for the businesses Raquel Heras works with, she says. Heras is a public relations professional in the cannabis industry who recently added psilocybin operations into the mix. ShroomFest is an early client.

On-site consumption was prohibited at the event, as security staff reminded several patrons bringing in their own drugs. Bags were searched, but contraband was not confiscated.

Employees of JamCare Medical were on hand to provide “medical, nursing and psychological care” in the event of a bad trip — “just in case,” says ShroomFest co-founder Eric Burden. “I’m trying to be respectful to the laws, the community and the mushroom.”

‘Celebrate the mushroom’

The event was meant to be a “celebration of the culture” as much as a chance to buy and sell goods, Burden says. Bands played at the nightclub adjoining ReelWorks, multiple bars were open for business and nearly two-dozen vendors sold food, clothing and art.

So much attention has been put to the use of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes — also part of Prop 122 — Burden says. He wanted ShroomFest not to be so “clinical” but a place “for people to have fun, to celebrate the mushroom.”

It was also a chance for businesses to support and learn from one another. Burden, who founded Denver Spore Company after the city decriminalized mushrooms in 2019, says the “biggest issue is credit card processing.”

Courtesy: Denver Spore Company

As with cannabis, national companies like Venmo, Visa, MasterCard, etc. and heavily regulated industries such as banks often don’t want to touch a business trading in what is still a federally prohibited substance.

Eric Sturm, CEO of E&B Supply, a spore and culture company, has had his payment processing and web hosting shut down once service providers discovered what he was up to. Even though it would remove several operational hurdles, Sturm says “I do not want to see [mushrooms] legalized” for sale the way cannabis has been.

“This is different than cannabis,” Sturm says. People can easily take too much, and shrooms are more debilitating.

Other entrepreneurs are similarly split on the idea of legalization. A man who preferred to be identified as “Chunk” says many people already treat psychedelics as a “cash grab,” an attitude he fears would worsen with full legalization.

‘Have you really journeyed?’

Another concern is the potential for people of color to be pushed out by government regulations that screen for criminal backgrounds, as happened with cannabis. Even with the proliferation of social equity programs — meant to undo the uneven prosecution of drug crimes that kept BIPOC operators from obtaining business licenses in the first place — the majority of cannabis industry executives are still white.

Chunk and his business partner, Leo Mendoza, say prejudice is already a “constant” within the world of psychedelics. Their operation, Shroom Sack, markets themselves as an “Indigenous and BIPOC” group of cultivators in part because they believe white organizers want to capitalize on the image of diversity while still treating non-white companies as less-than.

“We’ve done a couple of events like this,” Mendoza adds, “and we have noticed it.”

“People are posturing in the space,” Chunk says. “I hear them use these buzzwords, and it’s like, ‘Have you really journeyed?’”

Still, Mendoza believes legalization is inevitable.

Courtesy: Denver Spore Company

“I feel like cannabis already laid the path down,” he says. “For the government, it’s really about the money they can make.”

ShroomFest founder Burden thinks full legalization is “the way” to expand safe access. He views collaboration as crucial to fending off corporations who might want to invest big money into mushrooms.

“A big reason I’m doing ShroomFest is to give the grassroots guys an opportunity to come together,” Burden says. “This is the kind of stuff that keeps corporations out.”

Besides, there’s room for everyone.

Nearly “1.3 million people voted” for Prop 122, he says. “I can’t fill 1.3 million orders this year.”