It starts with a young boy in his room.

Max slams his door and gets sent to bed with no dinner.

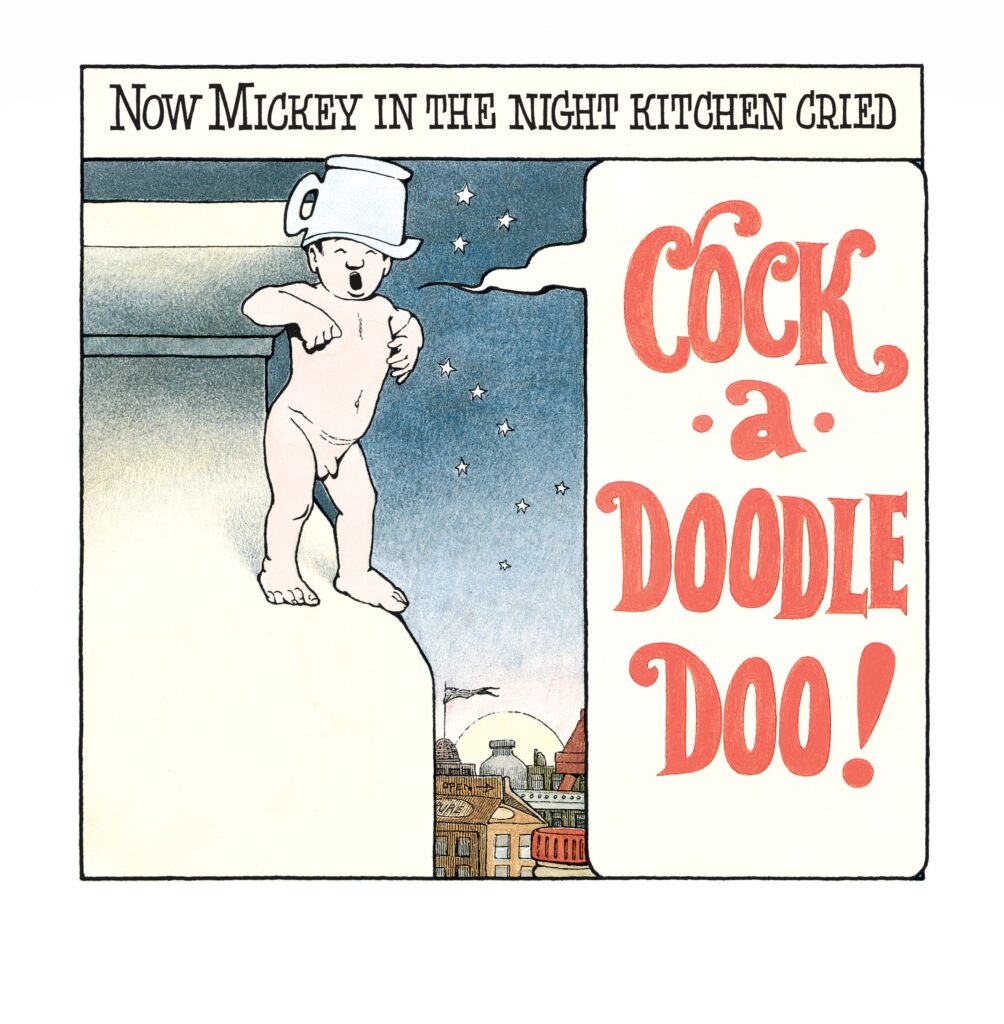

Mickey hears a late-night racket and falls into a vat of batter.

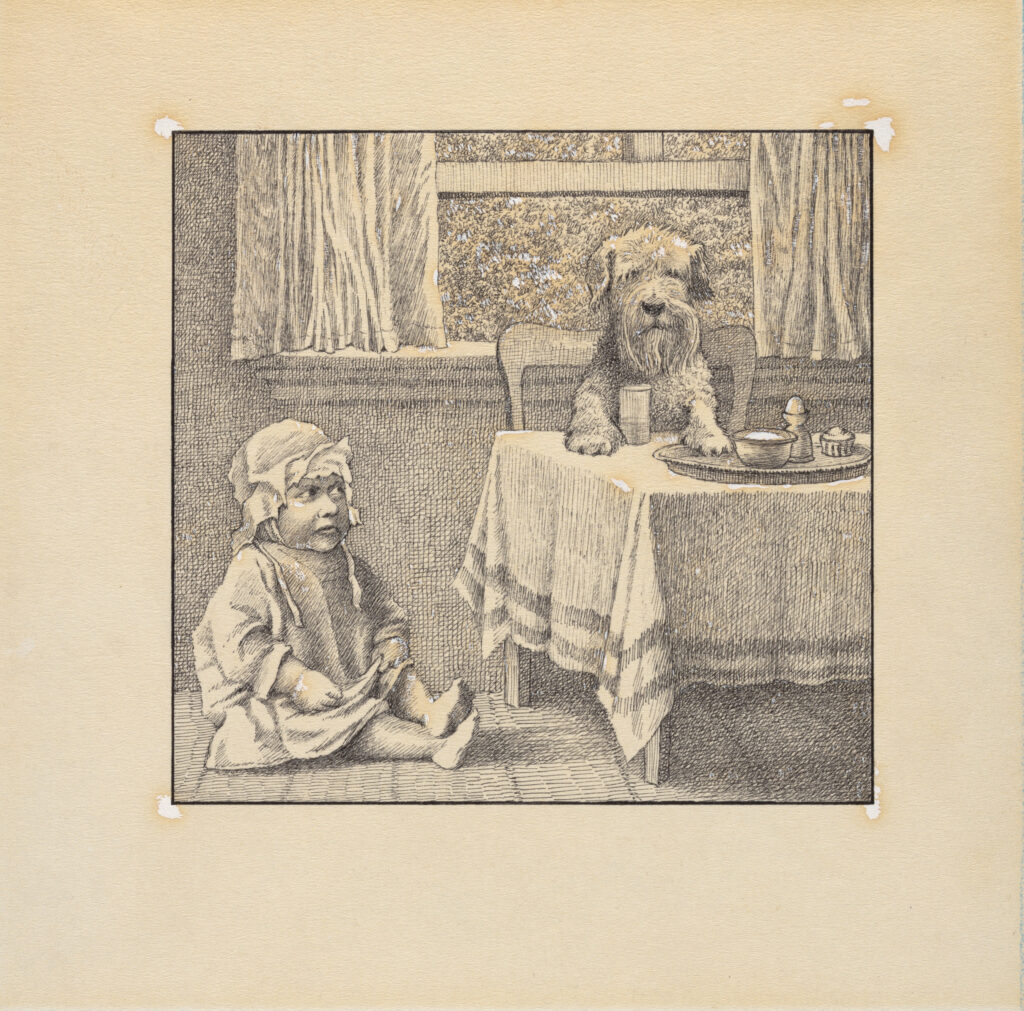

Kenny wakes up from a prophetic dream.

It’s no coincidence that so many of Maurice Sendak’s beloved books — Where the Wild Things Are, In the Night Kitchen, Kenny’s Window — begin in the bedroom during the odd and deep hours of the night. It’s the time when life falls away and parents are distracted, when darkness descends and the imagination loosens up. The time when the things that go bump in the night, go bump.

An outgoing exhibition running through Feb. 23 at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak, pays tribute to the man who never considered himself a children’s book author, but nonetheless won every prize imaginable for his children’s books. The show boasts more than 450 objects and artworks, tracing a rich creative life that extends far beyond his 1963 masterpiece.

Co-organized by the Columbus Museum of Art in partnership with The Maurice Sendak Foundation, the DAM exhibition is wholesome and filled to the brim with nostalgia; but it’s also dark, meditative and absolutely wild.

Sendak ticked away many of his own early days stuck in bed, riddled with illnesses that often separated him from the rest of the world. He was also a dreamer. He could quickly tap into the unreality of fantastic worlds, not quite lovely, but not quite nightmarish, and translate those complex qualities onto the page.

That sort of everything, all at once logic is the logic of childhood, and Sendak’s lasting legacy is found in his lucid depictions of kid characters. His Maxes and Rosies and Pierres are charming, daring and joyful; they’re also bratty little bullies sometimes. They get yelled at by their parents and they boss around their friends. So many children’s books show kids who they can be, littered with lessons and morals. Sendak’s books show kids who they are.

Where the wild things aren’t

Even though Sendak’s career is forever entwined with the success of Where the Wild Things Are, the museum doesn't let that interfere with other areas of his prolific creativity.

His whimsical processes and generous love for collaborators are on full display in the DAM exhibition. Sendak’s “fantasy sketches” adorn the walls, single sheets of paper where he improvised storylines while listening to a piece of music, typically classical. He sketched to Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. He revered Mozart; called him his god.

Born in 1928, Sendak grew up in a Polish-Jewish household in Brooklyn and deeply identified with the culture of Judaism, but remained secular throughout his life. His personal pantheon also included Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson.

He grappled with the darkest aspects of humanity from a young age. Sendak’s childhood was spent in close proximity to tragedy, with several members of his extended family dying in the Holocaust.

“I remember my own childhood vividly. I knew terrible things,” Sendak says in a 1993 New Yorker interview with Art Spiegelman. “But I musn’t let the adults know I knew … It would scare them.”

While biographical details can sometimes bog down an exhibition, the elements selected by co-curators Jonathan Weinberg and Christoph Heinrich illuminate Sendak with new clarity, revealing the man’s contours without overshadowing his work. He collected Mickey Mouse memorabilia and had a thing for the German romantics. He loved cake; he loved dogs; he loved his partner, Eugene David Glenn, whom he met in the 1950s and spent his life with.

Wild Things also pays heavy homage to Sendak’s many collaborators, including Ruth Krauss, Carole King, Spike Jonze, Tony Kushner and Dave Eggers.

Some of Sendak’s first successes were alongside Krauss, a popular children’s book author who had a massive influence on Sendak’s career — not just commercially, but in style and semantics. Her beatnicky writing freed Sendak to illustrate sentences like:

“Mud is to jump in and slide in and yell doodleedoodleedoo,” which appears in their 1952 book A Hole is to Dig.

She also encouraged Sendak to try new techniques with every book to avoid becoming boring, advice he took to heart. He rarely repeated himself and worked in a variety of artistic styles. When people clamored for a Where the Wild Things Are sequel, he’d tell them to go to hell.

Let the wild rumpus start!

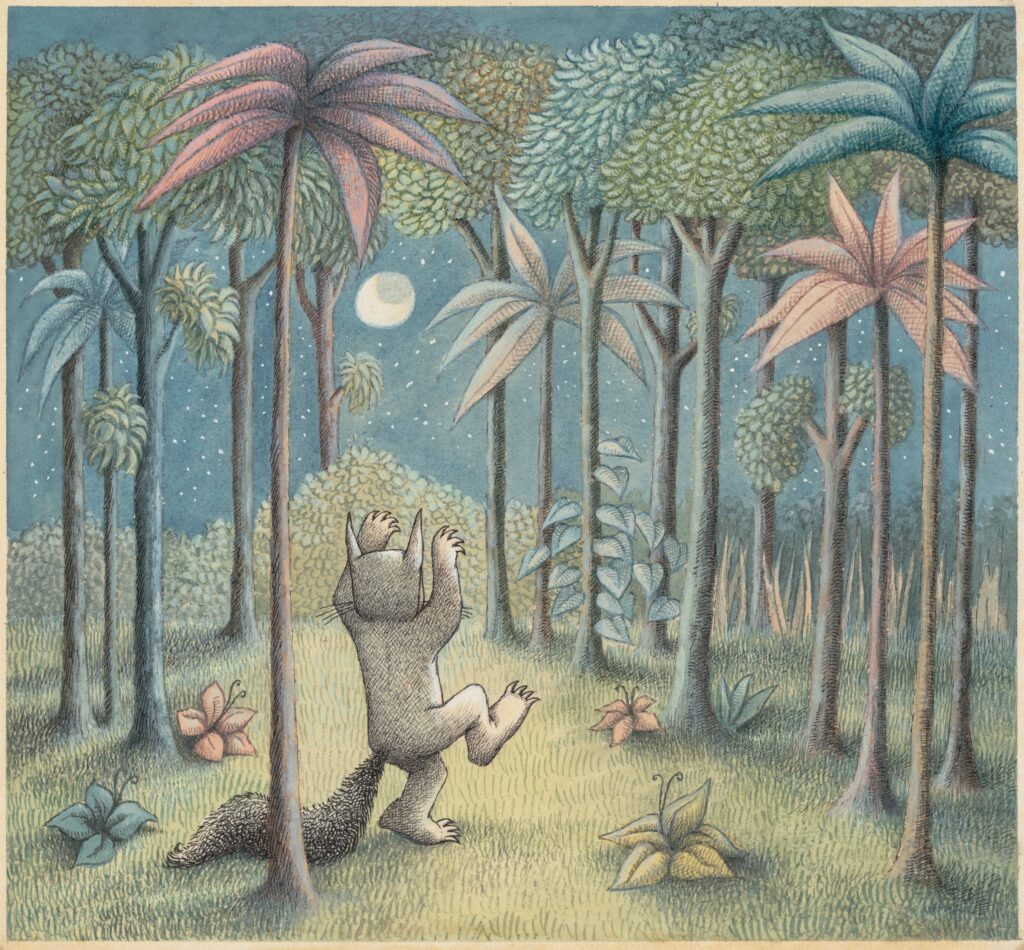

The natural centerpiece of the exhibition is the Wild Things room, a hushed space with dark teal walls. While other areas of the exhibition are layered with sketches, notes and ephemera, here the display is sparse, featuring only the original paintings for Where the Wild Things Are in the order they appear in the book. The shape of the room guides visitors from left to right, taking in each panel as if reading.

Sendak was approached with all kinds of deals for the wild things. They appeared on New York book fair posters, in a Bell Atlantic campaign, in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, in an opera. Almost half a century after the book was published, Sendak finally agreed to a movie directed by Spike Jonze in 2009, just a few years before the author’s death at age 83.

He had turned down a number of proposals by then, but Jonze presented a vision for the movie aligning with Sendak’s sensibility that children could handle the darker aspects of the world.

The one thing Sendak didn’t completely agree with was how the movie should depict the transition between Max’s bedroom and the fantastical world of the wild things. In the book, trees start to sprout from the bedroom floor, and gradually the room itself is transformed. But in film, everything that happens thereafter would be too obviously understood as a dream.

“There’s nothing worse than a movie that is all in somebody’s head or a dream,” Dave Eggers, co-writer for the screenplay, explains in the museum’s audio tour of the exhibition.

After much explanation, Sendak relented. The boy would have to leave the room.

ON VIEW:Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak. Through Feb. 23, Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Ave., Denver, $27