Longmont is accelerating on the road toward its goal of zero traffic deaths by 2040 with the launch of its Vision Zero program this fall, joining an effort to improve road safety along with cities across the globe.

Vision Zero is a community-focused approach with the goal to eliminate death and severe injury from car crashes, making roads safer for all users — pedestrians, bikes and cars alike.

As of last February, more than 50 cities in the U.S. have made the same commitment, according to the Vision Zero Network. Since that list was last updated, several Colorado cities — including Longmont, Fort Collins and Lafayette — have taken the initiative.

The results have been mixed at best. Nationwide traffic deaths reached an all-time high in 2023, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, and Boulder’s 10-year long program has led to stagnant results.

Longmont is confident it can use the shortcomings of Vision Zero in other communities to its advantage. They have a decade of both effective and ineffective strategies to draw from since the initiative first debuted in the U.S., and a network of cities to lean on.

“There’s a lot of sharing across communities, across the country, about what is working and what isn’t working and why,” said Longmont’s Vision Zero coordinator Cammie Edson.

Vision Zero takes commitment

One hundred and four people died in car crashes in Longmont from 2000-2023.

While safety improvements have been on the city’s radar since before the pandemic, Longmont officially adopted Vision Zero in April 2023 when the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law promised billions of dollars in funding for road safety programs nationwide.

But taking a Vision Zero pledge does not immediately translate to lower traffic deaths.

“Making a commitment to Vision Zero doesn’t necessarily mean suddenly all of the internal processes and ways you’ve been doing this work are suddenly changed,” said Tiffany Smith, program manager for Vision Zero Network, the organization behind the global effort.

It’s been a decade since Boulder committed to its own Vision Zero plan. While the city has reduced crashes overall, fatalities and severe injuries from car crashes haven’t really fallen.

In 2013 — the year before Boulder first set a goal to eliminate traffic deaths and severe injury by 2030 — the city reported 55 severe car crashes resulting in serious injury or death. According to Boulder’s principal traffic engineer Devin Joslin, there were 55 of those same types of crashes in 2023, three of which were fatal, despite there being 1,300 less collisions overall.

Part of Boulder’s lack of results, according to Alex Weinheimer who served on the Transportation Advisory Board (TAB) from 2019-2024, stems from where the city decides to invest their dollars.

“In the past, the city has chased high-dollar, one-off projects,” he said.

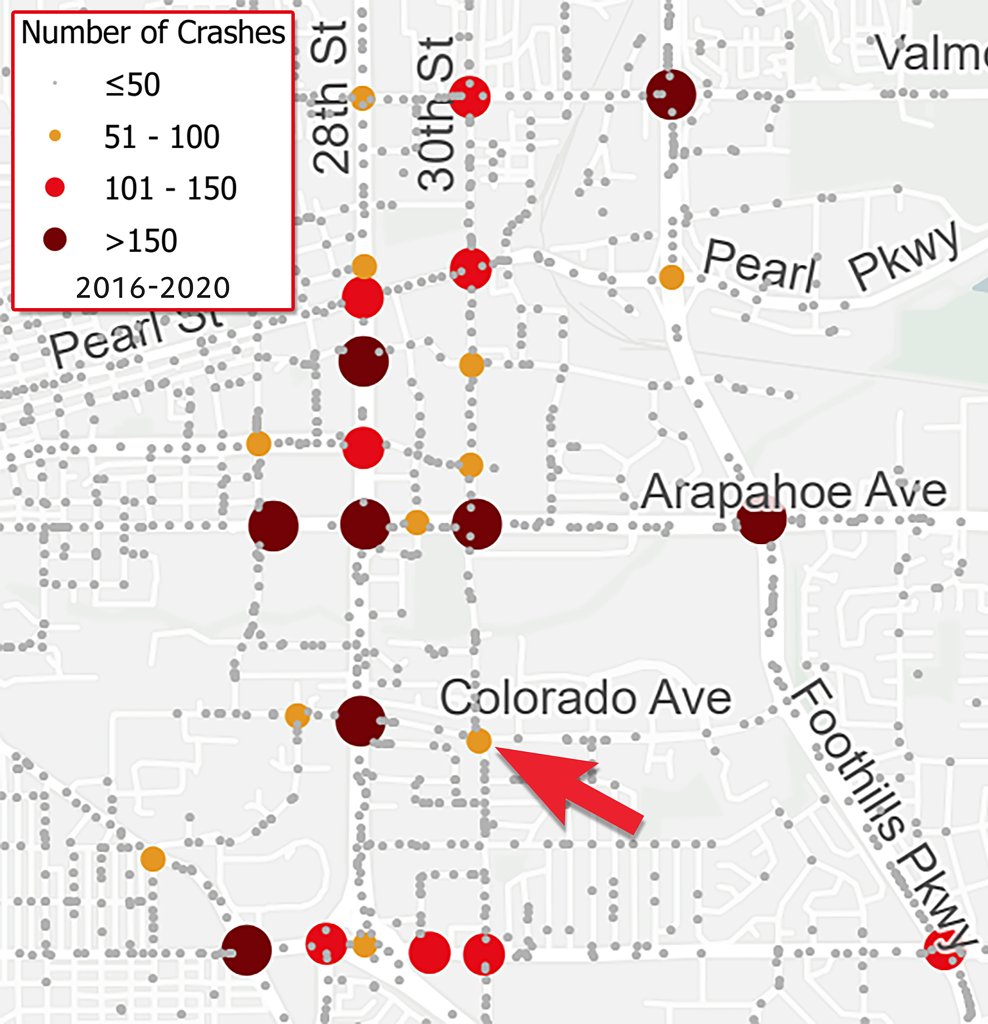

Take the intersection at 30th and Colorado Avenue for example. According to the city’s 2023-2027 Vision Zero Action Plan, there were only two crashes causing severe injury or death at that location from 2016 to 2020. Boulder recently completed a $15.9 million project — $8 million of which came directly from city funds — to construct a protected underpass for cyclists and pedestrians.

“We’ve got hundreds of severe crashes citywide, [with] some locations, especially corridors, that have higher numbers,” Weinheimer said. The ironic thing about that location [at 30th and Colorado] is there were … as many crashes at the signalized intersections north (Arapahoe) and south (Baseline) of there”.

It’s worth noting that, despite the amount of severe crashes reported at this location, it’s one of the busiest intersections in the city, according to the City of Boulder. More than 1,500 pedestrians and bicyclists travel through it per day, and there were 86 collisions — 18 of which involved a bike — at the crossroads from 2012-2018.

The 30th and Colorado underpass was one of eight projects to receive a 2024 Metro Vision Award from the Denver Regional Council of Governments in 2024.

“There’s been reward for chasing these big dollars and spending big. There hasn’t been an incentive structure in place to do the little things that might not be as flashy, but might be far more effective when it comes to capital projects,” Weinheimer said.

Course correction

A majority of severe and fatal crashes happen on Boulder’s arterial roadways — high-capacity urban roads that move motorists around, not unlike how our bodies move blood cells (hence “arterial”). The city’s most recent analysis of traffic collisions, the 2022 Safe Streets Report, revealed that 67% of severe crashes occur on these roads.

“What we recognized through that review… was that, it’s really about two-thirds of those severe injury and fatal crashes [occuring] on our arterial roadways,” Joslin said.

Toward the end of 2021, TAB developed the Core Arterial Network (CAN), a data-based map of Boulder’s busiest intersections and bike, pedestrian and transit routes. The goal was to identify corridors where the city should concentrate their infrastructure dollars to help reduce severe crashes systematically.

“What has changed now is the department is really focused on the strategic execution of projects that will transform our arterial streets,” Joslin said, “because that is where the data shows that people are most often getting hurt or killed.”

This data-driven approach has informed a number of lower-cost projects, including:

- the ongoing readjustment of speed limits, the first phase of which rolled out this summer;

- an update to signal timing practices, funded by a $1.2 million grant from DRCOG awarded in 2024;

- exploring protected left-hand turns and no right-turn-on-red rules at targeted intersections;

- and expanding the use of photo enforcement at signalized intersections in the city, made possible by a resolution passed by city council at the end of last year.

Boulder also received a $23 million Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) grant at the end of 2023, which will help fund a study into the effectiveness of right-turn slip lanes, enhance nine pedestrian crossing locations and make improvements to multiple intersections along 30th Avenue.

“Traffic signal timing updates, having more protected left turns, beginning to look at no right turn on red: Those are incredibly low-cost opportunities that are backed by data, and won’t win these big awards or pull in millions of dollars for one-off projects, but I think places where we’ll start to see some improvements,” Weinheimer said.

That shift in thinking is also occurring globally as more communities adopt Vision Zero.

“Where we see investments and complete streets, we notice the changes, but it’s much more piecemeal,” Smith said. “So it’s like, how do we move from this sort of fragmented approach to treating improvements, to really thinking systematically.”

Where the money flows

Improving road safety has been on Longmont’s radar since before the pandemic, but the funds to take action haven’t been available until recently, Edson said. The passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2023, which authorized up to $108 billion in federal funding for transit, opened the door for the city.

“Now there [were] the resources to also back up the work and make the work actually come to life,” Edson said.

Most recently, the city received $1.2 million in a grant from SS4A. “These funds will enable staff to gather essential data and develop a comprehensive, safety-focused Vision Zero Action Plan,” Edson said in a Sept. 10 press release, in addition to highlighting initial projects aimed at lowering speed limits in targeted areas around Longmont.

The city is in the process of building a map that identifies Vision Zero priority areas, according to Longmont public information officer Rogelio Mares.

In the meantime, officials have named 10 high-risk corridors as locations for traffic enforcement cameras, along with other areas with heavy pedestrian traffic, such as school zones and streets along city parks.

In the city’s 2024 Transportation Mobility Plan, Longmont also identified clusters of pedestrian- and bicycle-involved crashes — which account for 20% of car crash fatalities nationwide — along Main Street north of 9th Avenue, and at the Main and 3rd Avenue intersection.

Your move, Longmont

Longmont is not Boulder. On a given weekday, Boulder sees more traffic, with an estimated 60% of its workforce commuting from outside the city. A 2023 study found that 18% of trips made by Boulder residents are on a bike or scooter.

“We’re going to end up having different things we need to focus on, but it’s possible that we’ll have some similar things we need to focus on,” Longmont’s Edson said, “looking to what can we do from a systemic approach versus a spot treatment approach, so we can apply consistent benefit across so we don’t have that ‘They have it, why don’t we have it?’”

Longmont is still in the very early stages of developing its Vision Zero Action Plan — its second task force meeting was Nov. 18. Right now, conversations revolve around the numbers.

“We’re really focusing on the data,” Edson said. “What we know and don’t know and what additional data we need.

“Before we commit our limited resources, let’s make sure we understand where we need to be investing.”

One of the city’s first steps will be to initiate a traffic camera enforcement program of its own. At a Nov. 19 meeting, city council adopted an ordinance to install a network of cameras that will detect and photograph traffic violations in priority areas like school zones and around city parks, something that Boulder has been doing for decades.

The city still sees initiatives from other communities, including Boulder, as an opportunity to learn.

“They made a lot of mistakes when they did Vision Zero early on,” Edson said. “We’re all sort of reaping the benefit of learning from them, of what worked and what didn’t early on.”