Jacob Waltz has called Longmont home for a decade, but for the first time he’s thinking about leaving. Rising rent prices are outpacing his wage bumps, and last year he and his partner moved in with a coworker just to meet the rental property’s minimum income requirements.

A cheesemonger at King Soopers in Longmont, Waltz earns $22 an hour — nearly $7 an hour more than the $14.42 state minimum. Despite this, he’s still struggling.

“Honestly, I’m just kind of afraid,” he said. “If I end up losing my job for whatever reason, and end up having to go down to making something like $15 an hour again, there’s just no way we’re going to be able to sustain our living.

“What does that mean for the people who are making minimum wage?” Waltz said. “It’s not possible to build a life.”

Some municipalities have responded to Colorado’s cost-of-living by enacting higher minimum wages, something first allowed by state law in 2019. Denver workers now earn at least $18.29 per hour. Boulder County is on track to reach a $25 minimum wage by 2023, in unincorporated areas.

After declining to join the county last year, a coalition of Boulder County towns banded together to study the issue, with the goal of implementing a higher minimum for 2025. But now, that regional effort has collapsed, with only the City of Boulder planning to pass an increase this year.

Elected officials say more time and study are needed. They are hesitant to place cost burdens on small businesses who have opposed the effort, and fearful that wage increases will only contribute to the rapidly increasing cost of living.

“There’s a lot of hope and a lot of fear,” Longmont City Council member Sean McCoy said. “The fear is that they have gone through 2008, they’ve gone through COVID. Like, can you smack me with one more thing?”

Minimal job loss, negative impacts

Last year, city officials said they wanted a deeper economic analysis before deciding to join the county in raising the minimum wage.

Boulder, Longmont, Lafayette, Louisville and Erie together contracted ECONorthwest, an economic consulting firm, to analyze local data. The firm presented the potential community impacts of raising the minimum wage to each city council this summer.

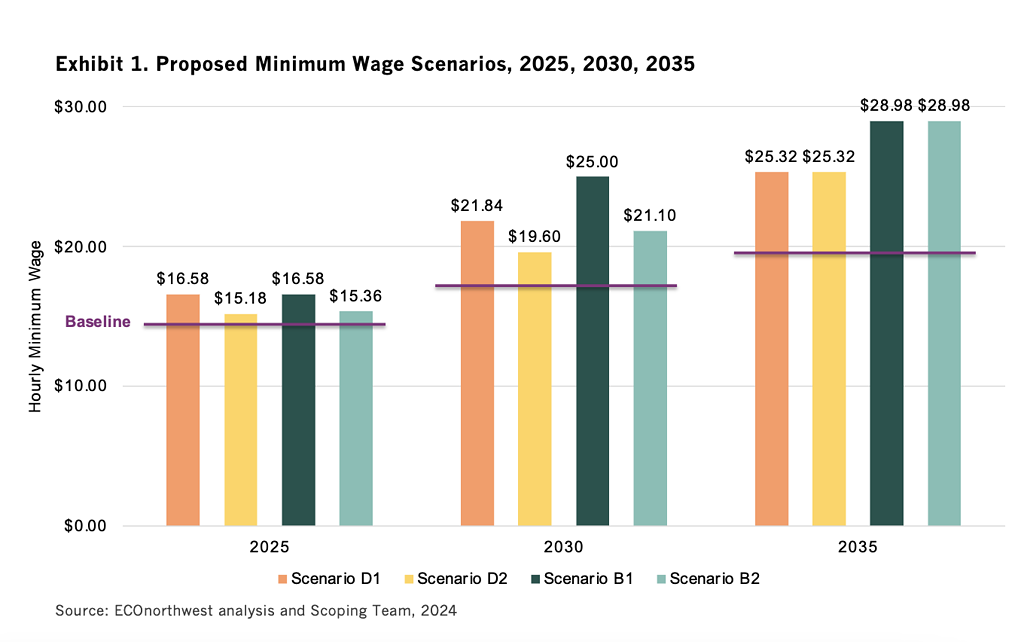

Four different timelines for increases were presented. Two options are designed to reach Boulder County’s minimum. The first track, B1, reaches the county’s minimum wage as fast as possible — 15% annual increase each of the next five years — matching the county at $25 by 2030. The second track is slower, matching the county’s wage by 2035 at $28.98.

Both Denver and unincorporated Boulder County’s minimum wages follow the Consumer Price Index. All four scenarios assume an average annual increase of 3% in wages.

The other two options follow Denver’s trajectory, with a $19.07 minimum in 2026 (Option D1) or a $25.32 hourly minimum by 2035 (D2).

Impacts to the local economy under the plans would be mixed, ECONorthwest Senior Economist Andrew Dyke said, but job and business losses overall would be minimal. The firm based their analysis on 10 cities who recently raised minimum wages with economic makeups similar to the five Boulder County cities.

“We wouldn’t expect a large loss of jobs as a result of a reasonably sized minimum wage increase,” Dyke said. “We would expect some increase in earnings [for workers], but there are trade offs. There are what look like many positive effects [and] some places with negative effects, but on the whole, we don’t see the big negative effects.”

A 2023 analysis in Denver showed that, since increasing the minimum wage in 2020, unemployment decreased more quickly than the rest of the state, while average wages increased significantly.

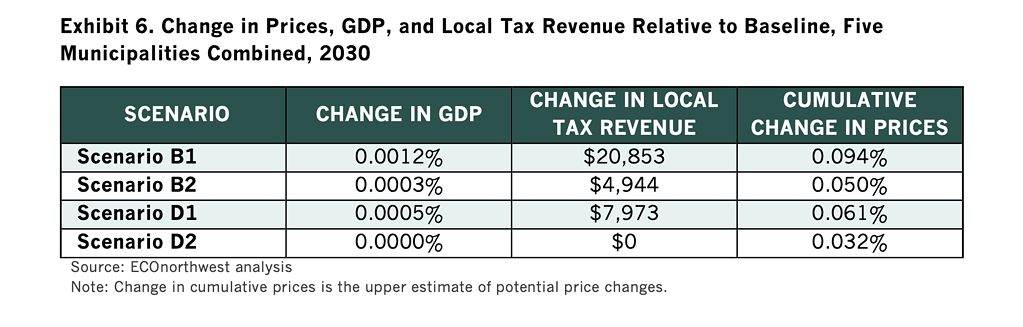

Projections from ECONorthwest show the cumulative increase in local prices will be 0.1% at maximum.

“Some businesses probably will fail, but not net,” Dyke said. “We would expect others to adapt and others to take their place.”

Boulder flying solo

The analysis has not convinced some business owners, who spoke at public hearings in their respective cities and other public venues.

“As many beloved businesses are still closing in Longmont and surrounding areas, some of us are finally regaining a small sense of stability,” Jean Ditslear, owner of 300 Suns Brewing in Longmont, said to elected officials on Aug. 27. “This proposal could be the final straw that forces many of us to leave or close.”

Elected officials tried to balance business concerns with those of other constituents: namely, the thousands of low-wage workers across each of their five cities.

“We’re trying to find a level in between the requests of some of these businesses to do very little or nothing, and our desire to get more money in the hands of low-income workers,” said Boulder City Council member Mark Wallach.

In the end, Boulder was the only city to take steps toward higher wages for 2025. A special meeting, public hearing and vote has been scheduled for Oct. 10.

Under the proposed plan, the minimum wage will increase 8% each of the next three years, after which another analysis will be performed to gauge impacts. This is a slight departure from ECONorthwest’s recommendations, with no immediate timeline to match the county’s minimum wage.

Economic analysis shows it is important to go slow, Dyke said. “I think Boulder’s approach is also exactly what we’d recommend.”

‘Waiting for everybody else’

In Lafayette, representatives want more community-focused data before they move forward.

“We decided to take our time and gather some additional information before really making any kind of decision,” said Lafayette Mayor Pro Tem Brian Wong. “I don’t foresee us making a decision in time.”

Wage increases can only be enacted Jan. 1 of each calendar year. If elected officials in Longmont, Louisville, Lafayette and Erie don’t act in 2024, workers there will have to wait until 2026 for a raise.

Longmont may defer the issue to the public, placing it on the 2025 ballot, according to McCoy. “I’ve heard several councilors say that this needs to go to the people,” he said.

Erie officials, who met on Sept. 17 to discuss the issue, are not moving forward with a wage increase, but may revisit the question in the future.

“I think we’re going to learn lessons from Boulder,” Mayor Justin Brooks said during the meeting. “I hope that we would know more about this perhaps a year or two from now to be able to reconsider.”

Louisville is also taking a wait-and-see approach.

“They are interested in seeing what happens regionally,” City Communications Manager Grace Johnson said.

“It appears sort of everybody is waiting for everybody else,” Louisville Mayor Chris Leh said during a Sept. 10 study session.

A small piece of the puzzle

For low-wage workers, time is of the essence. Based on the findings in the 2022 Self-Sufficiency Standard Report, an individual living in Boulder County needs an hourly wage of $22.18 to live without outside assistance, ECONorthwest estimates. Following current projections, that standard could reach $34.45 by 2025.

A few miles from Waltz’s King Soopers in Longmont, some employees at Safeway earn just $17.50. Despite the eventual pay bump that would come with a higher minimum wage, workers like Lola Pierce are still worried about affording their rent.

Pierce, who has previously struggled with homelessness, feels pressure to leave Longmont for somewhere cheaper.

“It’s not because I want to, it’s because that’s affordable and I can’t keep being on the streets,” she said. “If they raise the minimum wage, they need to make some choices, like on housing prices.”

A report released in 2023 estimated the average asking rent in Longmont to be $1,700, an affordable price only for those who make more than 60% of the area median income. That price is projected to shoot up to $2,050 by 2028, according to the report’s authors.

While a raise in minimum wage is not a panacea, it’s a step in the right direction, Boulder City Council member Lauren Folkerts said.

“I can’t say that I have ever had the opportunity to vote on a decision that would have a statistical impact on the wealth divide before. There just aren’t that many tools that do that,” Folkerts said of the city’s decision to draft an ordinance to increase minimum wage.

“Minimum wage is one tool, it’s not going to solve all the problems,” Dyke said. “But it can help make progress towards closing the wealth gap.”

While the rest of the county idles, Waltz plans to keep voicing his struggles until city officials step in.

“It’s sad to see our representatives not taking action on the problem,” he said, “but all I can really do is just continue to lobby for it.”

Tyler is a new reporter for Boulder Weekly. Click here to learn more about him.