It’s Jan. 16, 1985, and Boulder Mayor Ruth Correll is kicking off a 61-room expansion of the Hotel Boulderado. Lumbering in the crowd is a two-legged, wide-eyed human-sized rock with a permanent grin. His name is Buddy Boulder.

For silver-haired Boulderites, Buddy may seem like a fever dream. Perhaps he has escaped the collective memory altogether. But at one time, the anthropomorphic boulder was the face of the city’s tourism industry — or at least, that was the plan.

“Boulder mascot is a rock,” reads the headline of a March 9, 1984 Daily Camera article, announcing the winner of the Boulder Hotel and Motel Association’s Mascot Mania. The organization dreamt up the mascot contest, calling on Boulderites to name a city mascot that “represents the uniqueness of Boulder,” to put a face on their campaign to make the city more visible and attractive to tourists and business conferences.

Two years after his debut, Buddy Boulder was out of a job. After a handful of appearances, he began collecting dust at the Highlander Motel.

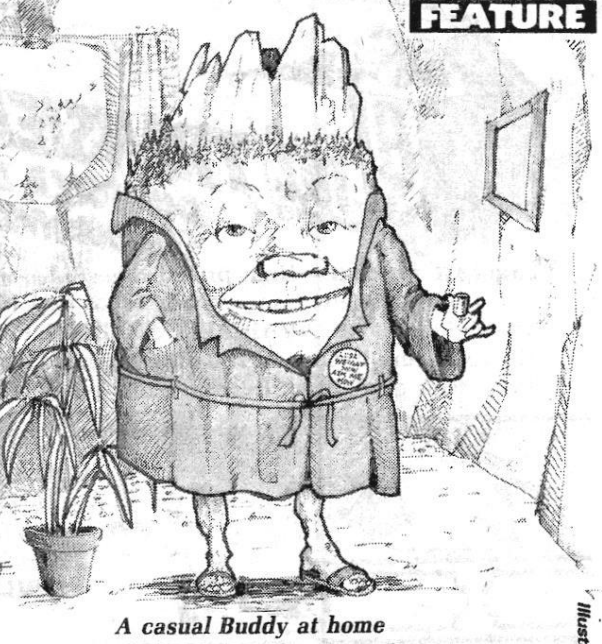

The quirky, tongue-in-cheek mascot was uniquely Boulder; a flippant character, born from the half-baked idea of a CU student, whose spiked Flatiron hair and stone dimples gave no impression he took himself too seriously. But Boulder was cool — maybe too cool — and Buddy was put in a corner, fading into the recesses of local minds.

Where is Buddy now? After months of searching, I’ve procured enough evidence to pronounce him dead — but there is still no body. While his fall from grace was spectacularly fast, his inability to stick and subsequent years in storage offer a glimpse at what Boulder was like 40 years ago.

The judge

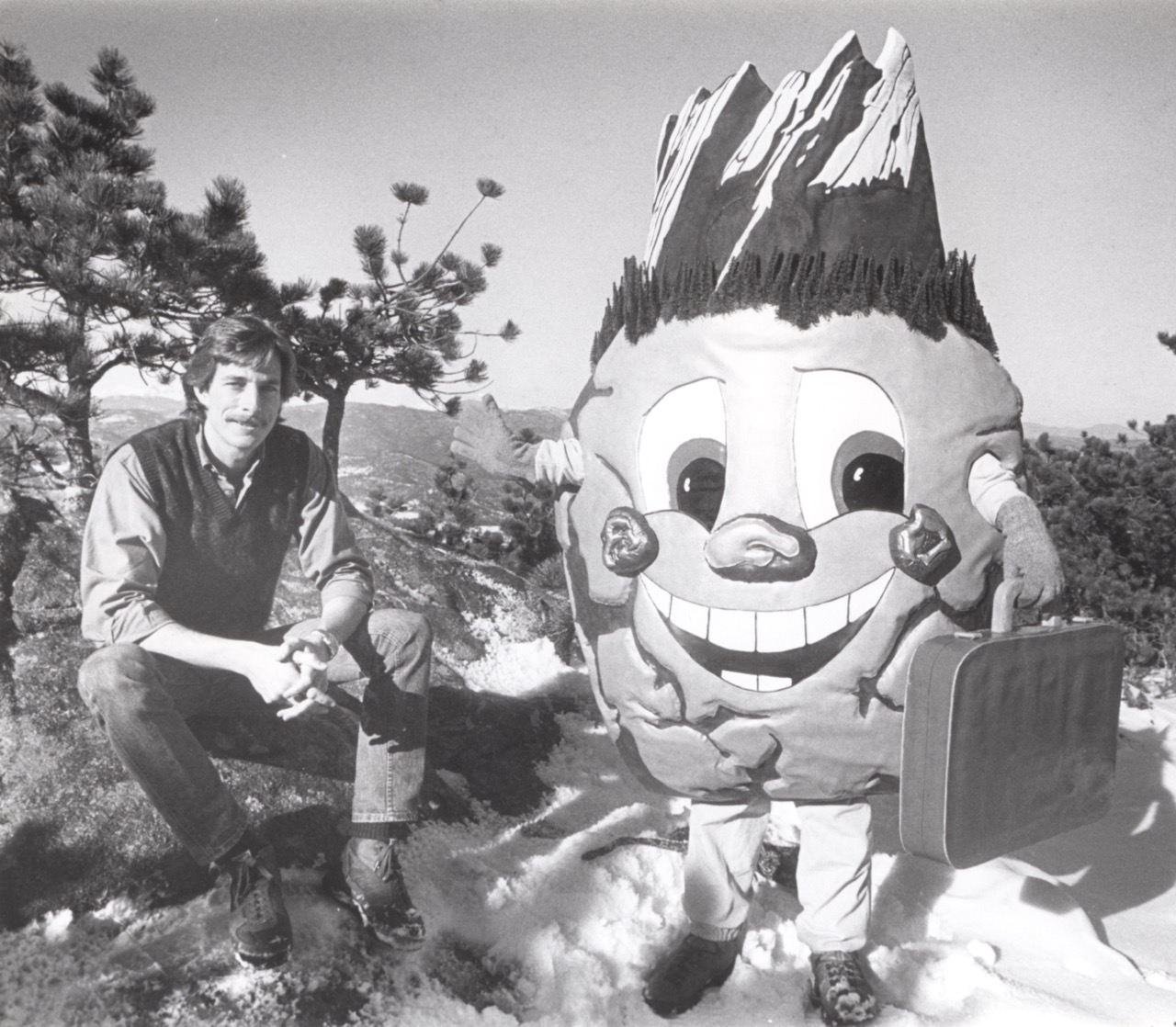

“It started on a whim, and it went out with a whimper,” says John Neiley, Buddy’s creator. A 24-year-old Neiley, still a jelly-legged fawn in the professional world, was contemplating an acceptance letter from CU’s law school at the time of Buddy’s conception. In the middle of the quarter-life “what’s next” crisis, Neiley saw an ad for a mascot competition.

As I discovered with most people’s memories of Buddy, Neiley’s recollection is fuzzy.

“It was probably more like a group of us, you know, roommates sitting around drinking beers,” he recalls. “And they're like, ‘Neiley, you can do this.’ I started thinking about it, and I'm like, ‘Well, it ought to be a rock.’”

The rest is geological history.

Neiley, now the Chief Judge for Colorado’s 9th Judicial District, scratched a lopsided drawing of a smiling, white-collar boulder carrying a stone briefcase, and gave him a resume.

“At that time, I was kind of in the job- hunting mode,” Neiley says. “I figured, well, if you want to get employed by someone, you should have a resume.”

Buddy’s elevator pitch read: “The fact that I am a solid citizen is taken for granite, and none of my friends are flakes… I never get stoned.”

The buttoned-up, oversized slab of rock fit the job description. At the time, the Hotel and Motel Association was trying to market the city as a destination for conferences, and had starry-eyed visions of the face of Boulder appearing at conventions and ribbon-cuttings. Neiley’s juvenile design and convincing Buddy-backstory won the judges over.

The organizations commissioned a professional costume maker. One year and $4,000 later, a fully grown bouncing baby Buddy was born.

The search

Buddy started his career side-by-side with former Denver Bronco Steve Foley at the Crossroads Mall for a “Super Sunday” sale. The Camera lists his busy schedule for January 1985: a ribbon cutting for the Hotel Boulderado expansion, a realtor luncheon and dinner at the Shrine Club of Boulder. He was gaining traction: Eldora (then Lake Eldora Ski area) and the Pizza Time Theater were showing interest.

He was catching on in local pop culture, too — though often lampooned as a drunk miscreant.

Buddy “was arrested today at Stapleton Airport in Denver after allegedly shouting obscenities and jumping into luggage carousels,” after a trip to the cocktail lounge, reads a summer 1985 spoof article in the Boulder Lampoon.

The piece goes on to quote a distressed Pillsbury Dough Boy, worried about his substance abuse problems: “I really love that little pervert. I never took him for granite.”

The Buddy craze didn’t last. “Mascot goes over like a rock,” headlines a May 11, 1986 article in the Camera. “Buddy Boulder is available. To put it mildly.”

From here, Buddy begins to evaporate from the Boulder consciousness. When I first set out to find the mascot, an afternoon at the Carnegie Library for Local History revealed no evidence of Buddy after that fateful spring day — save for a 2009 piece from the Camera about Boulder’s forgotten mascot. I was disappointed, but not discouraged; the few thousand words that had been written in his two-year life span were filled with names.

Where better to start, than with the brain behind Buddy?

But Neiley was a dead end. After he posed for a photo unveiling Buddy at an overlook just outside Boulder, he never saw the costume again. While Neiley claimed not to know where the body was buried, he sowed an anxious thought in my mind early in my search.

“My guess is it probably ended up in somebody's basement as a spoof,” Neiley said, “and probably found its way into a dumpster.”

Could someone actually be sinister enough to throw this lovable piece of history in the trash? I wasn’t convinced.

I did what any good journalist does, and began Googling. As it turns out, people who were professionals in the Boulder tourism industry the same year of the Chernobyl disaster are hard to find. Most search results came with “Thank you for so many years of service” press releases, or obituaries.

But obituaries have names, too. Which is how I found Kerry Lightenberger, whose late father Don Lightenberger owned the Highlander Motel, where Buddy was last photographed by the Camera in 1986.

While Buddy searched for a job, he sat in the lobby of the motel. Eventually, he landed in the Lightenberger’s garage.

“My dad liked the idea, and didn’t want to give up on the costume,” Lightenberger says. But instead of becoming a part of the workforce, Buddy was akin to the adult son that won’t move out of the basement.

He made appearances at Lightenberger’s annual Halloween party, in the back of her pickup truck during a St. Patrick’s Day parade, and most often as a punchline. But around 2000, he finally moved out — or rather, he was kicked out.

While moving her parents out of their home, Lightenberger recalled returning Buddy to the organizations who created him. This led me to Mary Ann Mahoney, then on the board of the Boulder Convention and Visitors Bureau, who became Buddy’s undertaker.

“We didn’t have any place to store him,” Mahoney says. In her mind, the true owner was the Hotel and Motel Association, but they didn’t want the deadweight of a giant costume.

When it looked like Buddy was headed for the streets, the Millenium Harvest House Hotel stepped up. Mahoney drove Buddy to the hotel, where they plopped him onto a luggage cart and wheeled him into storage.

“That’s the last I ever heard of Buddy Boulder,” Mahoney says.

It seems this is the last time anyone else saw him, too. The Millennium's general manager at that time, Dan Pirrallo, has no recollection of the costume living at the hotel — which in 2023 was turned into a pile of rubble to make way for student housing.

I hit a wall. Surely, someone who shared my infatuation with this costume must have cared enough to take Buddy in. But every time I drive by the Millennium's ruins on 28th Street, I can’t help but imagine the building crashing down around him, burying his lifeless form under a mound of steel and concrete.

In all likelihood, his demise came long before that. The fear I had from the start, each of Buddy’s temporary handlers echoed: At one point or another, someone probably threw him out.

Who killed Buddy Boulder?

As the search for a body continued, I kept coming back to the same question: Why didn’t Buddy Boulder work? Despite a few people clinging to the concept of a Boulder mascot for years, the short answer is that no one could stand wearing him.

“Nobody wanted to wear Buddy because it was hot to wear longer than 15 minutes,” Mahoney says. Whoever wore the costume could barely see out of the body, and his wide stature made doorways a constant obstacle.

“You needed an escort,” she adds, “It was like a two-person operation all the time.”

The one person bold enough to keep Buddy going was Bill Zollars. His name appeared in a few Camera articles as the man inside the Buddy costume, and had come up in enough of my conversations to warrant a phone call. If he didn’t know what happened to Boulder’s mascot, I didn’t know who else would.

Chances are if Buddy was at an event, it was Zollars. “We need you to wear this thing,” he says people would tell him. “You're the only guy that can have fun with it.”

“I’d do anything I want. I’d bump into people, I’d high-five people,” the former Millennial General Manager says. “You just have to go back and be a little kid.”

Despite Zollars’ playful Buddy persona, the public never truly embraced the mascot’s irreverent nature.

“There were a lot of people that thought it was hokey,” Zollars says, but “every mascot is hokey until somebody thinks it's really the coolest thing in the world.”

In a hippie town that became a hot spot for art and counterculture in the 1960s, a giant rock for a mascot seemed like the perfect on-the-nose commentary to reflect back at “the squares.” But in reality, the “the hips” thought they were too cool for Buddy.

“I don't think the arts community felt that he was a representation of the creative arts and craft community that they were,” Zollars says. “[If] you don't have, pardon my expression, the artsy fartsy people behind you in those types of things, then things sort of die.”

Buddy’s place in history

For better or worse, Buddy is a sliver of Boulder history. Without his remains, and likely an impromptu funeral in a trash compactor, he was never properly eulogized.

In my quest for Buddy, I held faith that someone along the way felt this artifact of Boulder tourism belonged in the Museum of Boulder. But in the museum’s collection of more than 49,000 material objects, there is no trace of Buddy, says the museum’s curator of collections and exhibits Elizabeth Nosek. For now, there’s a Buddy-sized hole in the museum’s collections.

“A museum is about preserving the object, not just for you and I to look at,” Nosek says, “but for… our great, great, great, great etc., grandchildren, to be able to come and see and to understand in a way they couldn't understand the story without seeing that costume.”

“I would fight for him to be accepted by the collection committee and the board. And I think he would, because he's uniquely Boulder.”

Around 25% of the museum’s collection is a costuming collection that was named an American Treasure in 2000 by the White House Millennium Council. The slew of artifacts includes the hunting dress of American naturalist Martha Maxwell, boy scout uniforms from over the decades, and even an old Mrs. Claus suit.

“Buddy would be able to tell stories of business and what people were trying to do to build the community,” regardless of how successful he was, Nosek says.

For now, and likely forever, Buddy’s story will be told with words, a few photos and a handful of old comic strips where the mascot’s mischievous nature is captured in cartoonish gags. Whether Boulder still thinks it’s too cool for the briefcase toting rock with a soft interior and exterior is now up to you.

See something, say something: If you or someone you know has information related to the whereabouts or final resting place of Buddy Boulder, please contact Boulder Weekly at [email protected]