Something must have been in the water in 1960. All around the world, filmmakers, either at the beginning, middle or the end of their careers, swung for the fences.

In Japan, Akira Kurosawa spun Shakespeare’s Hamlet into a corporate thriller with The Bad Sleep Well. In India, Satyajit Ray made his first directly political movie with Devi. In Sweden, Ingmar Bergman’s rape-revenge story, The Virgin Spring, blazed a new genre trail. In Italy, Federico Fellini gave the world La Dolce Vita, while in France, Jean-Luc Godard reinvented the game with Breathless. Back here in the states, Alfred Hitchcock struck a new chord with Psycho. And across the pond, Michael Powell buried his career with Peeping Tom.

It’s worth singling out those last two for comparison. Both Hitchcock and Powell enjoyed career heights in the 1940s and ’50s, both became synonymous with lush Technicolor dreamscapes, and both tested the limits of cinema’s ability to transport viewers into their characters’ point of view. Both also enjoyed artistic and financial success.

But in England, Powell (who worked with Emeric Pressburger under the production label of The Archers from 1943-59) was beginning to see that success wane. He was bursting with creativity and innovation, but it was becoming harder to get projects off the ground and convince the moneymen to take a risk. So the director split amicably with Pressburger — the two would remain friends for the rest of their lives, even working together on subsequent projects — and struck out on his own to tell the story of a boy who loves watching so much that he kills for it. The film destroyed his career.

Meanwhile, back in the states, Hitchcock’s career surged to new heights with his own story of a disturbed young man with a predilection for voyeurism and murder. And considering both men, played by Anthony Perkins in Psycho and Carl Boehm in Peeping Tom, display a vulnerability that is unsettling to the audience and attractive to the women in the respective movies, the films feel like Robert Frost’s two roads diverging in a yellow wood.

Why Peeping Tom failed where Psycho succeeded is explored in The Criterion Collection’s newest 4K+Blu-ray. The set includes two commentary tracks and a bevy of interviews (including one with Thelma Schoonmaker, Powell’s widow) about the film and the filmmaker, enough that one could spend more time fixating about everything outside of the frame than what’s in it — as I seem to be doing here. It must be the capitalistic impulses baked into our very being that we have to find where the line between failure and success lies.

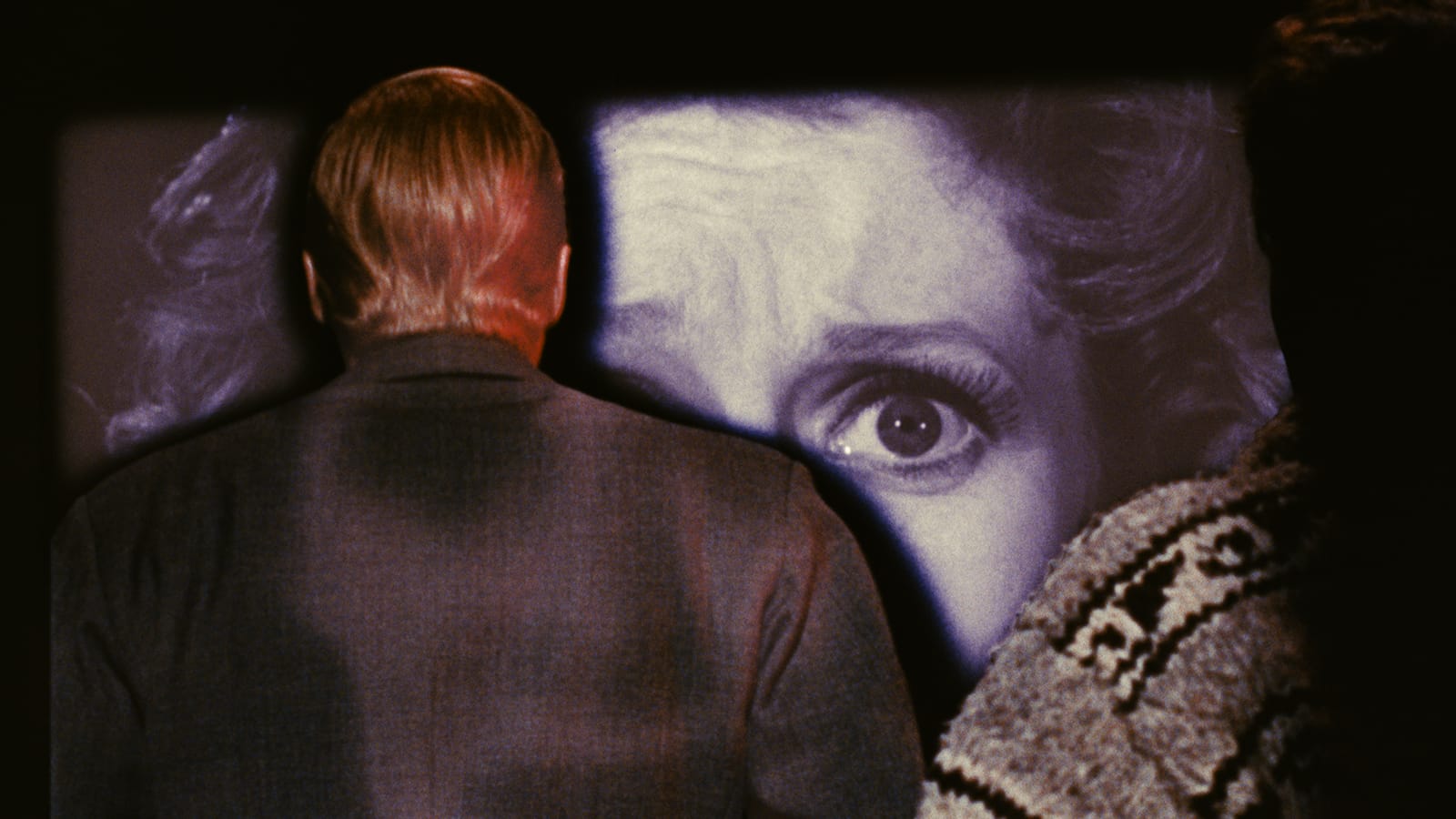

Or it might be because as great as Peeping Tom is, it tackles such an icky subject that it’s difficult to praise Powell’s on-point presentation. Look at how cinematographer Otto Heller employs color; consider how screenwriter Leo Marks uses the blind Mrs. Stephens (Maxine Audley) as a foil for consummate watcher Mark (Boehm). Don’t they feel somewhat lurid? Immensely clever and appropriate, yes, but lurid nevertheless.

Peeping Tom is like no other. The story revolves around Mark, who acts and talks like a loner but is surrounded by women and work. He’s only alone in his mind. Mark is a freelance photographer living in a London flat above landlord Mrs. Stephens and her adult daughter Helen (Anna Massey), who has eyes for Mark. She’s also a little on the lonely side, and in another movie, theirs would be the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

But this is not that movie. Mark is disturbed, and swirling around town is the mystery of murdered women, all who perished with their faces screwed up in terror as if the last thing they witnessed was the most horrific thing imaginable. You know Mark is the murderer from the get-go without Powell tipping his hand — he’s that good of a storyteller — but you don’t know how the women died or what scared them so. Nor do you know what scarred Mark and led him down this dark path. You will, by the movie’s end, but you won’t feel good about it. Powell has no interest in assuaging the audience’s feelings or letting them know it’s all right and everything will be fine.

And for that, the British critics called for his head and suggested the film be flushed down the sewer. Powell’s run as one of Britain’s finest filmmakers came to a grinding halt.

Forty years after Peeping Tom’s release, my college professor screened the movie as part of our Intro to Film class, and my fellow students were equally up in arms. I, too, was rattled by the film but also impressed and intrigued. Peeping Tom is an odd entry point into the cinema of Michael Powell, but it was mine, and it sparked a love affair with his movies these past 20-plus years.

Peeping Tom was also my entry point into the world of stories where troubled young men are not easily dispatched with resolution or explained away strictly for comfort, convenience and commerce. (Psycho became a franchise while also giving birth to the slasher genre.) Peeping Tom shows you the ugliness of the world not simply to scare you, but to prepare you for what’s out there. For that, I will always be grateful that Powell put it all on the line. It cost him a lot, but it gave us so much.

ON SCREEN: Peeping Tom is available May 14 on 4K+UHD from The Criterion Collection.