Thumbing through the local music section at Paradise Found in downtown Boulder, you’ll find rows of shiny, shrink-wrapped gems ready to change your brain chemistry forever. Maybe it’s the yacht-pop yearning of Denver duo Tennis, the synth-drenched death metal of Blood Incantation, the jamgrass jubilation of Leftover Salmon — or some strange new alchemy that hasn’t yet cast its spell on you.

But it’s not witchcraft bringing these sick sounds to your earbuds. The music we obsess over is the result of labor, and industry experts say the job is getting tougher. As the rising cost of living continues to pinch households across the U.S., the delicate dance of recording, touring and promotion is becoming an increasingly complex math problem for working-class musicians on the Front Range and beyond.

“It’s more expensive than ever to create new music,” says musician, nonprofit professional and artist advocate Kirsten Vermulen. “The assumption is that folks have a home studio and anybody can make music today and become famous on TikTok. But if you are really dedicated to the craft, working with the industry here in Colorado, you’re going to spend a good $10-to-$20,000 to put a full album out. Coming up with that kind of capital when you’re piecing together shows as a regional artist is really challenging.”

That’s why Vermulen volunteers as executive director of the Colorado chapter of Sonic Guild, an Austin, Texas-based music patronage nonprofit founded in 2013 whose mission is to ease the financial burden for working performers. Borrowing from the long tradition of patrons underwriting “high art” like orchestras and symphonies, the idea is to leverage a broad base of donors to help make the job of musician a more viable career path through grants, professional support and performance opportunities for emerging artists — including Boulder-bred acts like Pink Fuzz and Megan Burtt.

“There are very few artists in Colorado who are able to solely focus on their art, which is frustrating and disappointing given the talent we have here,” Vermulen says. “The artists I have the pleasure and privilege of engaging with through Sonic Guild are juggling multiple careers.”

‘I’d be really afraid’

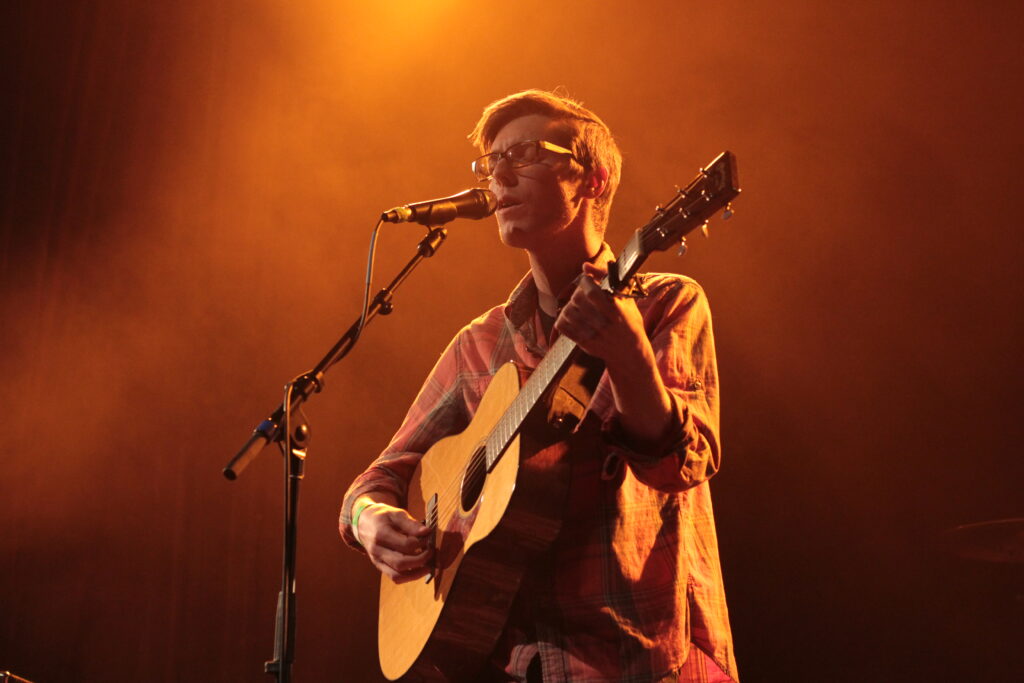

Denver-based indie folk artist Patrick Dethlefs knows something about that juggling act. Gigging throughout the region since the 2010 release of his bright and bouncy debut full-length Stays the Same, the 34-year-old from Kittredge supplements his income by putting in roughly 25 hours a week as a sales associate at Patagonia.

“I’ve been doing [music] for a while, so I’m able to keep a consistent amount of shows on my calendar — that’s really helpful,” Dethlefs says. “But if I were starting out, I’d be really afraid, at least at this moment, to just be trying to rely on music.”

Of course, making music your livelihood isn’t impossible. Local favorites Big Richard, an all-women bluegrass ensemble that has been burning up the festival circuit in Colorado and beyond since 2021, rely largely on income generated from the band and solo work to get by. The outfit’s Grammy-winning cellist Joy Adams says she manages to stay afloat by pursuing all opportunities with a similar urgency — whether that’s a New Year’s Eve show at Nashville’s famed Ryman Auditorium or a gig the next day at Busey Brews Smokehouse & Brewery in Nederland.

“That’s just the name of the game,” Adams, 36, says. “To be a successful musician and pay the bills, you have to let go of this idea: ‘Oh, I’ve made it, and I have this standard of gigs now.’ You need to take any gig and give it the same good energy you gave everything else.”

Even with a packed calendar of shows, when it comes to the ability to patch together a living on music alone, many local artists who don’t have the name recognition of a marquee act like Big Richard say the scene ain’t what it used to be. That’s especially true in Boulder County, where a heady mix of sky-high rents and dwindling opportunities have left some homegrown acts feeling squeezed like never before.

“I was talking the other day in the green room with a couple bands who played in the ’90s out here, and they said it used to be that you could find a gig on a Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and those gigs would pay [up to] $300 per person,” says Dave Kennedy, founder and CEO of the Boulder nonprofit venue Roots Music Project. “Now they’re getting $100 to $200 per person, and there’s just not as many gigs.”

The Colorado Paradox

In some respects, the uphill battle faced by Front Range musicians isn’t unique. The health of local scenes varies from region to region and changes with the times, but as streaming juggernauts like Spotify continue to demonetize the artform writ large — offering an average payout between $0.003 and $0.005 per stream — the prospect of making music your day job is becoming a pipe dream for many creatives regardless of where they live.

“No artist is making money from Spotify. They’re making a little bit more on Apple Music or Tidal or whatever, but the only way a band actually makes money is if you buy a T-shirt or a record,” says Lafayette resident Ben Sooy, 39, frontman of local emo outfit A Place for Owls. “Even if you just buy the album digitally on Bandcamp or iTunes, that’s a hell of a lot more money actually going to the artist than if you just stream it.”

On top of these universal roadblocks to fair compensation, Colorado presents a cluster of unique challenges when it comes to making a living as a working musician. One of these is also the state’s greatest asset: the mountains. Isolated by a yawning gulf of rugged topography, the prospect of touring can be a difficult proposition for artists here.

“We played Treefort [Music Festival] a couple years ago, and we just didn’t realize how far away Boise was — or Salt Lake City, for that matter. It’s a long way to go,” says Michael Seman of the Loveland-based noise rock band Shiny Around the Edges. “It’s not like the Northeast or the Midwest, where it’s really easy to hit major markets within a short period of time.”

With this tangle in mind, Vermulen says Sonic Guild is looking to help Colorado acts take their show on the road through a new grant program she hopes to launch this year to underwrite touring expenses. It’s a model that first took root in the nonprofit’s Seattle chapter, where she sees a key difference in terms of cultural mindset and community support.

Citing the so-called “Colorado Paradox,” a term used by some economists to describe the state’s ability to attract out-of-state workers while struggling to incubate homegrown talent across industries, Vermulen says our local music scenes suffer from a similar problem.

“We don’t identify in Colorado as a music community, even though we have a really high concentration of successful independent venues,” she says. “Red Rocks is typically the first or second most-visited venue in the world — it is a part of our lifestyle, but I do not believe it’s part of our identity, something we believe culturally is worth preserving, like it is in places like Seattle and Austin.”

‘All things in common’

When it comes to the value of that preservation, Seman says it’s a two-way street. In addition to his work as singer-guitarist in Shiny Around the Edges — a long-running art rock project launched with his wife Jennifer Koshatka Seman near the turn of the century in the thriving DIY music community of Denton, Texas — the 56-year-old musician also works as an assistant professor of arts management at Colorado State University, where he studies the economic impact of local music ecosystems.

“I tell city leaders you don’t want a music scene that’s super successful just because you may have the next superstar,” he says. “I mean, that may happen, but today you have this collection of people who are running your economy: lawyers, teachers, designers, architects — they’re all involved in music scenes, and it keeps them in the city.”

According to Seman’s research, the calculus is pretty simple: When local musicians thrive, so do the places they call home. He says municipalities can help by financially supporting all-ages venues and music collectives like The Vera Project in Seattle and the privately funded Music District in Fort Collins.

Back at Roots Music Project, which offers up to 12 days of rent-free space per year through the Boulder Arts Commission waiver program, owner Dave Kennedy says artists can do themselves a favor by recognizing their own value.

“Stop undercutting each other. Raise your rates. Hold out for more, because too many artists will do it too cheap. Don’t be the bargain band,” says Kennedy, who plays guitar with local blues legend Rex Peoples. “There’s not a union for local bands, but they sure could use one. It’s so separated. Artists aren’t talking to each other, but they should compare notes more and say, ‘Yeah, we need to raise our rates together.’”

That sense of a shared struggle motivated Sooy of A Place for Owls to launch a mutual aid nonprofit for DIY musicians on the Front Range, with the stated mission of “holding all things in common” by pooling funds for vinyl pressing, merch production and more. He’s waiting on tax documents from the state that will allow the organization to begin fundraising in earnest, but considering the mission to emphasize collective care in a world built on the profit motive, he arrived at a name early on: Holy Fool.

“Capitalism teaches you that other artists are your competition, and it’s a zero-sum game: If they get a win, that means you lose,” says Sooy, who works as a staff musician at The Table Church in Lafayette 20 hours a week. “That’s just not the way real life is actually supposed to work. The healthiest communities of creative people are ones where they are your family and collaborators; they’re rooting for you to win. Every win for somebody else in your community is kind of a win for you.

“Most capitalists will look at that and be like, ‘Well, you’re a dum-dum. You’re an idiot,’” he continues. “But that’s actually the holiest and most righteous way to be in the world."