The Colorado River has served as a centerpiece for so much of the mythology and literature written about the American West.

From books like John Wesley Powell’s Exploration of the Colorado River and Its Canyons to Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, the 1,450-mile waterway has captured the attention of writers and photographers for more than a century.

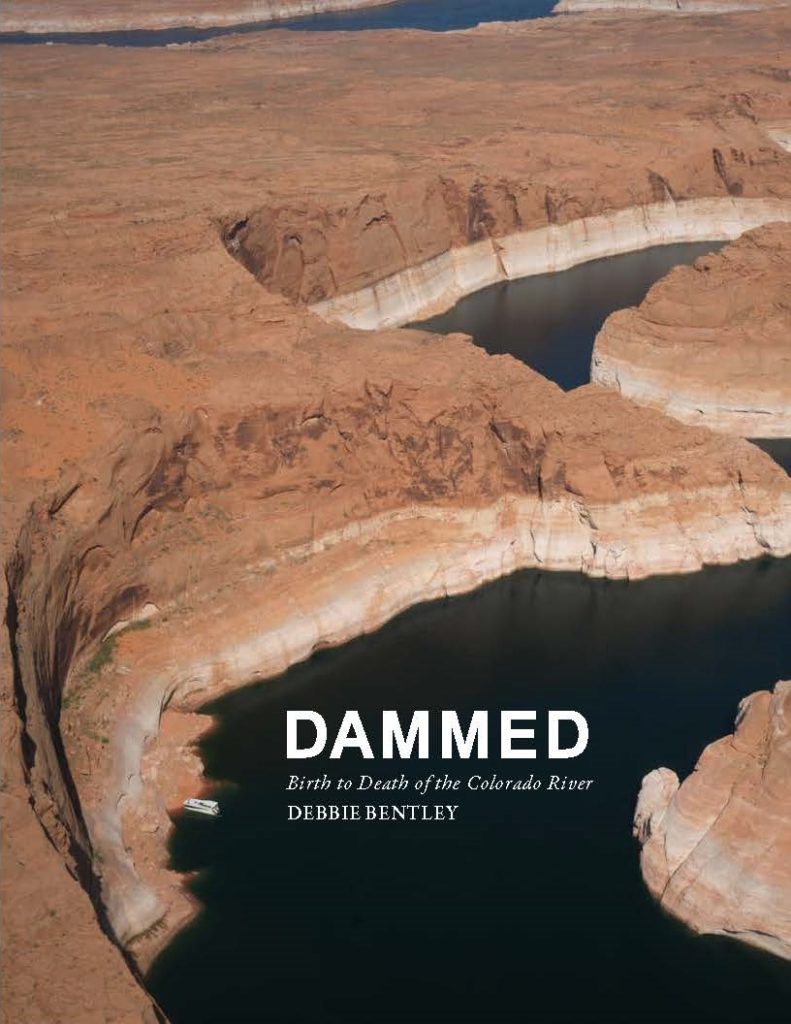

Add Colorado-born photographer and scribe Debbie Bentley to that long list. The Wiggins-based artist spent years following the path of the river for her new book of photography and writing, Dammed: Birth to Death of the Colorado River, published by Daylight Books. Featuring stunning images that are both gorgeously composed and depressing at the same time, she highlights the dire state of the essential waterway.

With her photographs, infographics and historical research, Bentley shows how climate change, poor water-management practices, overuse and the effects of aridification have endangered the river that provides water for almost 40 million people and 5.5 million acres of farmland from the Rocky Mountains to the Mexico border.

“To deliver such large amounts of water, the Colorado River has become one of the most controlled rivers in the world with 15, soon to be 16, dams to impound and divert its waters on the main stem alone,” she writes.

In the introduction, Bentley explains how “unbridled growth” in the West and Southwest, coupled with mandated water deliveries from a compact more than 100 years old, have “stretched the water supply to its limit.”

‘The Grandma Moses of photography’

Born and raised in Colorado, where she spent a lot of time with her grandfather fishing the rivers and streams of the state as a child, Bentley says she always felt a connection to the water here.

“We wandered around all over the place,” she says. “That’s really what piqued my interest.”

Bentley came to love photography early in life when she was handed down her grandfather’s Kodak Pony Model C after his death. Despite her affinity for making pictures, she didn’t start getting serious about photography until later in life, about 15 years ago.

She and her husband owned a high-purity piping business in California for about two decades. After closing it down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Bentley picked up the camera again. “I’ve referred to myself as the Grandma Moses of photography,” Bentley says.

A trip to the Salton Sea put into motion the project to explore the river, its reservoirs, dams and the people in its path.

In 2018, she traveled to Pilot Knob, near Winterhaven, California, where, in 1905, Colorado River floodwater diverted through a poorly made irrigation system unintentionally created the saline lake known as the Salton Sea. The river was patched up two years later. At the turn of the century, the lake began drying up due to decreased inflow and evaporation, releasing toxic dust and causing devastating biological and ecological damage.

After Bentley saw that, she set a goal to provide a visual reference of the sheer size and length of the main stem of the Colorado River and explain how the complicated dams work along the route.

A management problem

When it comes to the story of the management of the Colorado River, including attempts at balancing fish populations and other control measures,Bentley’s book shows as much as it tells. With the photos of the bathtub rings at lakes Mead and Powell as just two examples, her photos illustrate how downstream the river is losing water volume.

“At the end of the day, this isn’t a natural flow,” Bentley says. “There’s just fallout from managing a system like that.”

For decades, the river’s water delivery agreements have been based on politics rather than science, she argues. In fact, “there was science that was ignored,” Bentley says.

According to Bentley, in the early days of the river’s management, interests across the American West, most prominently in California, saw the water running all the way to the sea and decided it would be better used for irrigation and residential water.

“That snowballed at a governmental level,” she says.

In her book, Bentley quotes from John Wesley Powell addressing a government body charged with overseeing irrigation, all the way back in 1893. “Gentlemen, it may be unpleasant to me to give you these facts,” Powell said. “You are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply these lands.”

More than 130 years later, the Colorado River — which once reached the Gulf of California in Mexico — now peters out several miles before the sea.

Bentley sees the Colorado Division of Water Resources as treating the river relatively better than their counterparts downstream. That may partly be due to it running through Rocky Mountain National Park, a crown jewel of preserved outdoor spaces in the state.

“I think Colorado does attempt to pay more attention to ecosystems within the state,” she says.

As an example, she points to Price-Stubb diversion dam on the river near Palisade, which was decommissioned and is now a fish ladder that allows migrating fish to pass.

“I feel like because the river is ours, there does seem to be greater care in Colorado,” she says. “Here, it’s still beautiful.”

ON THE PAGE: Dammed: Birth to Death of the Colorado River book launch with Debbie Bentley. 6-8 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 8. Colorado Photographic Arts Center, 1200 Lincoln St., Suite 111, Denver. Free.