Perusing the aged wooden bookshelves of Boulder’s Carnegie Library, you’ll find boxes full of records from when the Boulder Star made the news. The local history archive holds a treasure trove of stories about the twinkling annual holiday display — from its construction to the very first lighting, and the joy it brings to Boulderites each year.

But the word that might appear most among the newspaper clippings is “vandalism.”

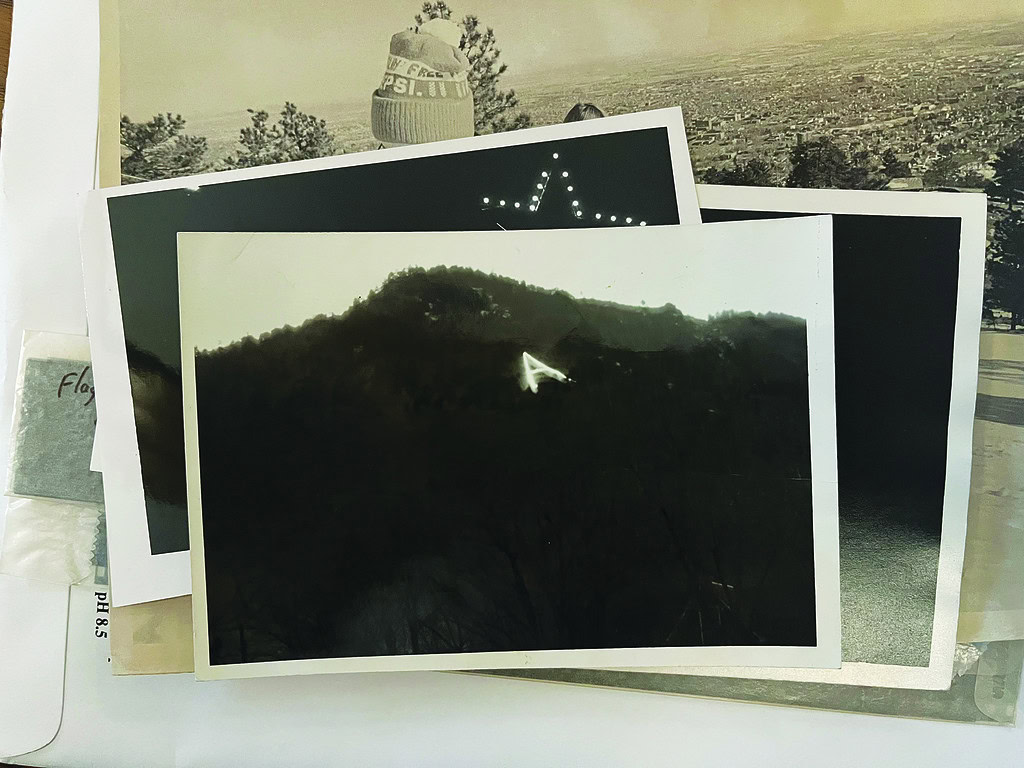

The first lighting was a few days before Christmas of 1947. The pranks began soon after. It started out playfully: In 1951, the star was rearranged into an “A” — presumably by students at Colorado State University, formerly Colorado A&M. In an effort to not be outpaced, several students from Colorado School of Mines rearranged the star into an “M” in 1958, which landed three freshman students with suspensions, $100 fines and 10 days in jail.

Apparently the punishment was not enough to deter other, more sinister vandals. The following year, the star’s wires were cut and pulled down, dozens of the bulbs smashed or stolen, and throughout the mid-50s the bulbs were repeatedly painted red, which the Daily Camera hypothesized was related to Communist ideology.

“People who are purposefully taking out their aggressions on the Boulder Star,” says John Tayer, president and CEO of the Boulder Chamber. “That’s an infliction of pain to our entire community.”

Courtesy: Carnegie Library for Local History

A new tradition

The star, now managed jointly by the chamber and the city, was constructed in 1947 after several years of delays from World War II and deliberating how to get electricity up Flagstaff Mountain. Its shape was originally outlined in toilet paper, resulting in a star 259 feet from top to bottom and 125 feet across, with approximately 400 light bulbs.

The beloved seasonal tradition, which now begins on Veterans Day and ends the first Sunday after the New Year, is meant to inspire hope and joy during cold winter months.

“It’s a wonderful community treasure,” Tayer says. “On a winter night, you’ll look up there, and it gives you a lift.”

But for some, the Boulder Star seems to be a beacon for making trouble.

By the 1970s, hijinks at the star were as much a holiday tradition as its lighting. The display was rearranged into a peace sign during the Vietnam War, a “#1” when CU Boulder won the national college football championship in 1990, and strangely, the outline of Minnesota in 1993. But the city continued to light the star each year and performed its own sanctioned rearranging each spring, making a cross for Easter for two decades until the practice was put to an end after legal disputes determined it violated the separation of church and state.

Those weren’t the only times the star became a political flashpoint. In the 1980s, the City of Boulder kept the star lit for the 444 days that the Iranian Hostage Crisis lasted. That same decade, the star drew the ire of at least two separate environmental advocacy groups, one of which sent a note to the Daily Camera citing energy waste, ecological damage and protest over the United States’ presence in the Middle East. They also called the star “an eyesore.”

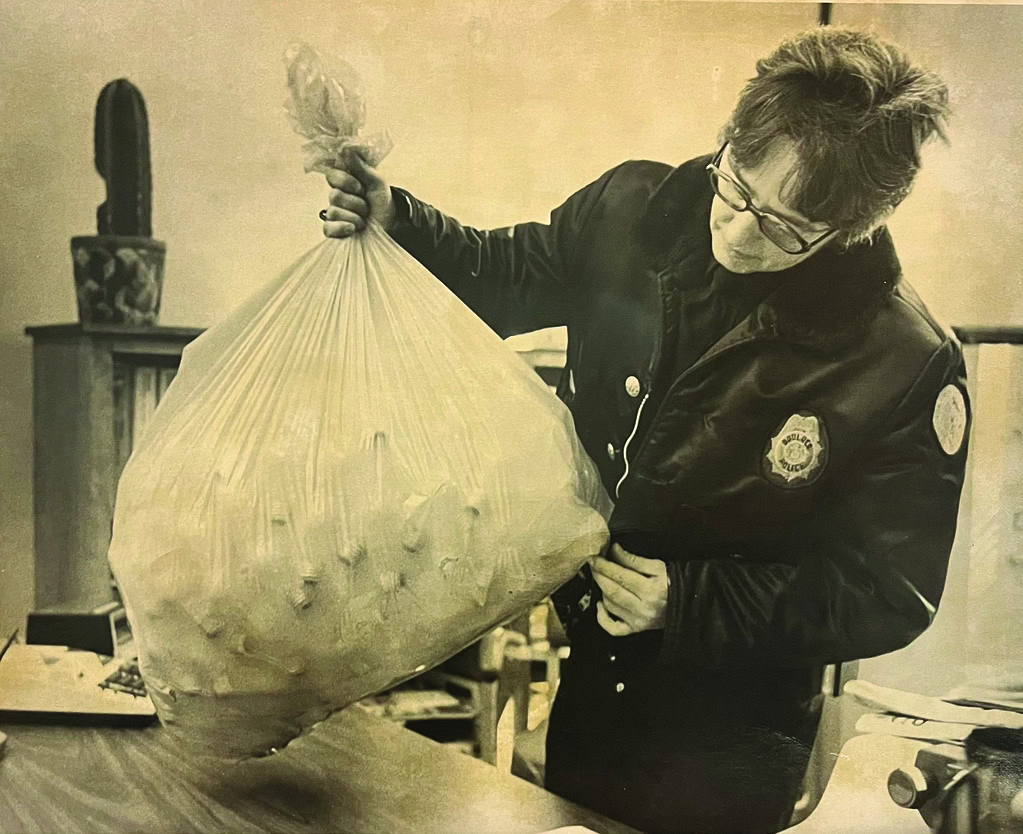

After one of the groups unscrewed all the bulbs in protest, donations and support poured in for a $2,000 restoration project. Boulder and Fairview High School student councils publicly pledged to work with the repair teams, and cash donations flowed from residents across town, including a piggy bank full of coins from two young girls.

Unusual activity surrounding the star has historically been reported by residents within minutes, with the aforementioned peace sign protest in 1969 prompting 35 calls in one evening, the Daily Camera reported. On such calls, people would often call the display “my star” or “our star.”

“It’s very clear that the Boulder Star is beloved in our town,” Tayer says. “People have opinions on every detail.”

The Star Man

Perhaps the worst case of vandalism happened in 2001, when a trespasser cut into the light panel and smashed the circuit breaker with a rock, causing the entire star to go dark for the night.

For most of the new millennium, electrician Craig Reynolds got the call when the display was damaged. The chamber reached out to several local contractors in 1998, looking for help repairing the star before the season. Reynolds, who owns Longmont-based Lord & Reynolds Electrical Services, says he was the only one to show up.

He quickly became known as “The Star Man,” keeping a vigilant eye from his home window. When something looked wrong, Reynolds would head up the mountain with a crew of friends, family and handy volunteers.

“It was such a passion for me,” he says. “In the beginning, it wasn’t a big deal. I didn’t even know what the star really was, but after a couple of years, it’s like, ‘I take care of this thing.’”

Reynolds took his responsibility seriously, making sure not to travel out of town between the time the display turned on in November and off in January. He went up the mountain on early mornings, cold nights and even one Christmas Eve when he noticed a significant number of the lights had gone dark.

“My parents were in from out of town, and I said, ‘Well, you know what? There’s a problem up there, I need to go,’” Reynolds recalls. “Sure enough, half the star was out, and I had to fix it — got it back on, though.”

The City of Boulder took over maintenance of the star in 2023, a change Reynolds is happy about. He loves the star, but the city can enforce trespassing rules and vandalism penalties that officials hope will deter people from trying to damage it.

The city has closed off the area to protect the nature and wildlife on Flagstaff Mountain. The mountain itself has a steep grade with loose, uneven terrain, making it unsafe for climbing.

Despite the rules, desires to get closer to the star persist, particularly with local college students who pass around stories of hiking up to the star and stealing a light bulb after getting, well, intimate among the lights.

Just a few nights after the lighting ceremony this November, three trespassers were spotted scrambling their way up the mountain to sit beneath the display. Some things, it seems, are slow to change.

‘It just makes you happy’

The holiday tradition has expanded to include an annual art competition run by the chamber, with local artists submitting applications to create a work depicting the star that will then be used on postcards, a puzzle and the wine bottle label for the star wine, created and sold annually by BookCliff Vineyards in North Boulder.

Kristen Ross is this year’s winner among 34 applicants. Her work is vibrant and colorful, depicting the star from an angle that includes iconic views of the Flatirons and Longs Peak.

Ross can view the display from her home window, and says seeing it lit up all winter long brings her joy.

“It’s just a nice little reminder how good of a community Boulder is and how we can get together and build something that’s not even necessarily practical,” she says. “It just makes you happy.”

Ross recalls how meaningful it was to see the star being lit up throughout the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The chamber has illuminated the star at times outside the holiday season to honor important events or commemorate tragedy, like after the King Soopers shooting and the Marshall Fire the following year.

The star’s status as a symbol of hope and inspiration is reflected in its new theme song, “Beacon,” by local composer Jeffery Nytch and performed by the Boulder Philharmonic during this year’s lighting ceremony.

“It’s just one of these glorious traditions that unites our community,” Tayer says.

It’s undeniable that, positive or negative, the Boulder Star inspires strong reactions from the town. In its 77th year, it still shines brightly from Flagstaff Mountain, its storied history of pranks, attacks and rebuilding coming together to make a uniquely Boulder tradition.

Reynolds, the Star Man, has seen and felt first-hand just what the star can mean to people. Throughout the years, his mailbox has been stuffed with thank you cards expressing gratitude for his dedication and people sharing personal stories about the significance the tradition plays in their lives.

“It was really nice,” he says. “It made me even more committed.”

Reynolds himself proposed to his wife while sitting on a rock beneath the glowing lights of the star, looking out onto Boulder, knowing that at that very moment there were probably hundreds of eyes looking back in their direction. It’s no wonder she said yes.