It was a January Saturday after one of the season’s first big snows, and I had managed to talk two day-trip-averse companions into heading to Winter Park.

We left early enough (or so I thought) with spirits high. But before we even made it to I-70 from Denver, we were crawling along at a snail’s pace. Four hours later, we were finally arriving, albeit a bit deflated.

“It’s still early,” I remember thinking. “We’ll be out there in no time, and we’ll hardly remember this hellish drive.”

I was wrong. We spent another hour or so circling the free and paid parking lots: “There has to be an open spot somewhere,” we said over and over.

Wrong again.

After giving up on the lots, we eventually found a spot on a side street in town and hoofed it to a shuttle pick-up spot. The line was long, and when a minivan drove by offering a ride for 20 bucks, we paid up.

By the time we were finally about to take our first run down, it had been nearly six hours since we left home, just 70 miles away. It was a beautiful day and the snow was great, but I can’t say the vibes ever fully recovered — especially after it took us another three hours to get home.

This experience isn’t emblematic of every day trip, but it is the type that’s had more and more of my friends swearing off driving to the mountains on weekends.

“It’s not worth the traffic or price for someone who just isn’t that good at it,” wrote one r/COSnow Redditor who said they haven’t skied since the early 2000s. “I feel like it has to be a passion for those willing to spend that much time and money.”

The winds of change are blowing through Colorado’s ski resorts, and they’re not showing signs of letting up. Pass prices are rising, more people are hitting the slopes, and seasons are getting shorter. At the same time, resorts are building faster lifts and expanding their terrain.

“There are numerous people that would say, ‘I don’t like the way it’s changing, it wasn’t like it was before,’” said Joel Hartter, founding director of the Masters of the Environment and Outdoor Recreation Economy program at CU Boulder. “But I work all over the U.S. in resort communities and recreation hot spots. That perspective is always there. Things are different from what it used to be… That is going to continue.”

‘An enormous jump’

The price tag on hitting the slopes is getting steeper — both for season and day passes.

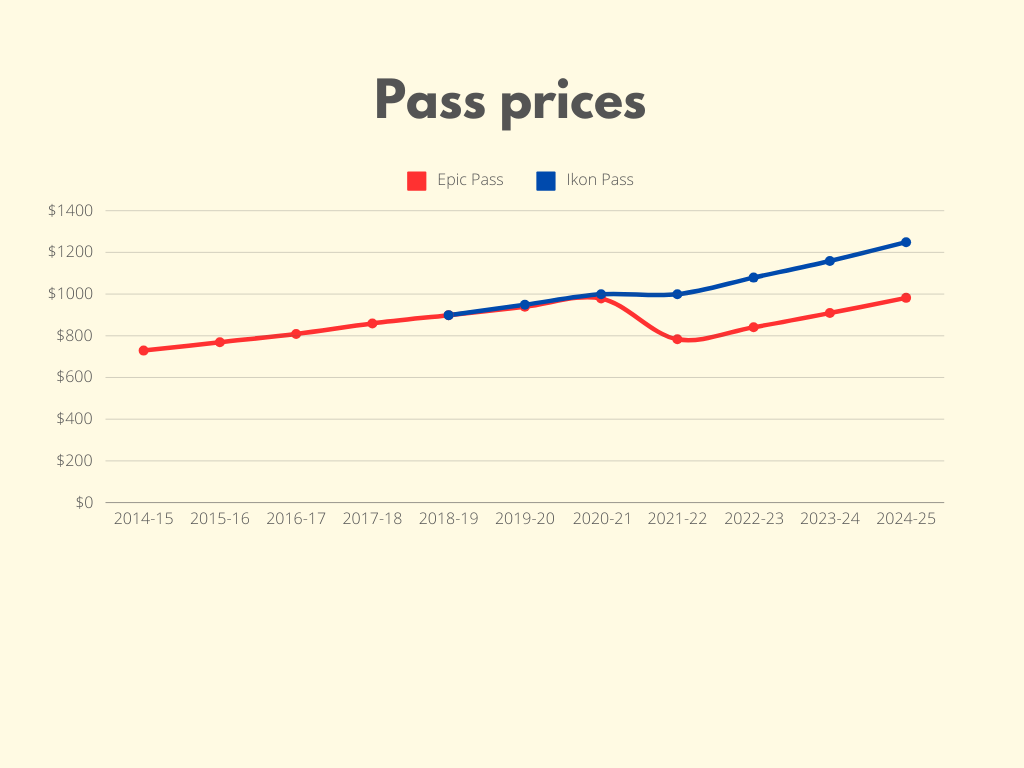

The Epic Pass, launched by Vail Resorts in 2008, saw a $982 starting price tag for the upcoming season. That’s 25% more than it was for the 2021-22 season, when Epic cut its price (though it’s only $3 more than the season before the price slash).

The pass has also opened the door to more terrain as the company acquires more and more slopes across the country. The pass now grants access to more than 50 resorts across the world, five of which are in Colorado.

The Ikon Pass, which includes more than 60 resorts, has gone up in price by 39% since its 2018 inception and $90 just in the last year.

“That is an enormous jump,” Hartter said, “and that has all sorts of cascading effects.”

On one hand, increased revenue allows resorts to make “costly upgrades that skiers now expect” such as high-speed chair lifts, advanced snow-making capabilities and resort amenities. On the other hand, Hartter calls it “the biggest issue for consumers,” as the barrier to entry becomes higher.

“It really comes down to becoming an exclusive pastime,” Hartter said.

Still, he believes the bubble isn’t likely bursting on a large scale.

“I don’t think we’re there yet,” Hartter said. “I don’t know what that would be. There’s a lot of factors.”

The shift to multi-resort passes also reduces overall cost for frequent skiers while also serving to drive up single-day lift tickets. With day prices for resorts on Ikon and Epic often running more than $200, it only takes as few as five days to break even on a season pass — a move by resorts to lock in revenue before the season begins.

If you were to ski once a week from January through March, it would cost you about $80 per trip on the Epic Pass, or $104 on Ikon. If you had the more limited version of each pass, it would cost you $60 per day on Epic or about $70 on Ikon. Bump up your number of days skied to 20, and it amounts to $46 per day on the full Epic Pass or $37 on Ikon.

Average season pass sales have more than doubled across the past decade, according to a National Ski Area Association (NSAA) spokesperson, and sales for 2023-24 exceeded the 10-season average by 75%.

That’s served to make resorts more crowded and has also changed who’s skiing.

“The influx of out-of-town skiers using multi-resort passes has altered the atmosphere at some resorts, impacting the local vibe and community feel,” Hartter wrote in an email response to follow-up questions.

A 2023 Slate article claimed the pass duopoly had “ruined skiing” and turned the sport into a “soulless, pre-packaged, mass commercial experience” that favors jetsetters over ski bums and workers.

“Ruined and also made it affordable,” another Redditor said in response to the Slate article. “I’ve lived in Colorado my whole life and couldn’t afford to ski a single day til I was 15. Now season passes are somewhat affordable compared to what they were in the late 80s.”

Ski’s a crowd

Despite the rising costs, skiers and riders are largely still paying up. The last three years had the highest visitation on record for the Rocky Mountain Region (made up of six states including Colorado), according to the NSAA.

But the most recent season saw some dips. Visitation declined regionally and nationally after a record-breaking 2022-23.

“Nationally, skier visits are trending up in the long-term, and the 2023-24 season came in above-trend, despite the dip from the previous season,” NSAA spokesperson Tonya Riley wrote in an email. “While skier visits dipped last season across the country, the scale of those decreases were highly varied, especially when considered in the broader historical context.”

Colorado had an estimated 14 million skier visits for winter 2023-24, a decrease of about 5% from last season’s all-time high, according to Colorado Ski Country USA, a nonprofit trade association representing 21 ski areas. That’s still the second-highest skier visit total on record, according to the organization.

Some of the decline, Hartter said, is a return to the norm. After the pandemic, “[people] came back in force,” he said. “We’ve seen this all across the outdoor industry, where after the initial surge, there’s been a sort of normalization.”

Vail Resorts saw a 9.5% drop in visitation for the 2023-24 season, according to its fourth quarter report, and season pass sales through Sept. 20 for the upcoming season decreased by about 3% (though sales dollars were still up 3%). The company attributed the dip in visitation to “unfavorable conditions” and industry normalization.

In response to growing crowds (and discontent from skiers), resorts are putting up major money and implementing new rules.

“We’ve seen tremendous infrastructure investment with high speed [lifts] and so forth to get people up the mountain and return them,” Hartter said. “All of that plays into trying to reduce the congestion down at the bottom and spread people out across the mountain.”

Vail Resorts in 2021 announced it would spend more than $315 million on projects to “materially reduce wait times, increase uphill capacity and create more lift-served terrain.” That included a dozen new high speed lifts, on-mountain restaurant expansions and new lift-serviced terrain.

According to the company, it was its “largest single-year investment into the guest experience” at the time.

Copper’s Timberline Express was upgraded from a four-person lift to a high speed six-pack that debuted this season, according to the resort. Alterra-owned Winter Park’s master plan involves annexing 358 acres of terrain and adding gondola service from town. It also includes parking upgrades and more snowmaking.

Even smaller, independent resorts have been making upgrades despite fewer resources.

“Limited capital compared to larger conglomerates can pose a challenge,” a Loveland Ski Area spokesperson said in an email, “but we’ve made significant investments over the years, including replacing four lifts in the past decade and implementing numerous other improvements like installing four new snow guns at Loveland Valley ahead of this winter.”

Other efforts target traffic and parking woes.

Dynamic pricing that makes it cheaper to ski on weekdays and off-peak parts of the season also aims to spread out crowds, according to Hartter.

Arapahoe Basin, a local favorite sold to Alterra in November, is implementing a parking reservation system for 2024-25. Spots must be reserved in advance on weekends and holidays and cost $20 — unless you carpool; then it’s free.

After implementing a parking reservation system in 2020 and doing away with it the following year, Eldora now charges $10 for single-occupancy vehicles on peak days. The resort also hands out free tickets for the RTD bus going from Boulder to Eldora on weekends and offers a free shuttle on weekends.

The Winter Park Express, a seasonal Amtrak between Union Station and the resort, dropped prices by more than 40% this year as it aims to increase ridership.

‘The number one threat’

There’s one looming problem companies may not be able to spend or innovate their way out of: climate change.

The NSAA calls it “the number one threat to the snowsports industry.”

“We’re going to have shorter ski seasons,” Hartter said. “Certain terrain is going to close; resorts are going to close earlier. We’re going to have earlier snow melts. We’re going to have rain, it’s going to rain earlier, which melts everything out as well.”

As a result, he expects resort conglomerates will begin diversifying their offerings — not just across different locations — but also in terms of activities, getting a hand in summer recreation like rafting and golfing and building up off-season infrastructure.

U.S. ski areas lost an estimated $5.5 billion from 2000-2019, a study published this year in Current Issues in Tourism found. In the 2050s, ski seasons are projected to shorten between 14-33 days and 27-62 days, depending on emissions, the study estimates.

Vail Resorts, which attributed its decrease in visitation to unfavorable conditions, reported that its snowfall for western resorts in North America for the 2023-24 season was down 28% from the prior year.

“Sustainability success is not a zero sum game; if we do nothing, we all lose,” NSAA spokesperson Riley wrote in an email. “That’s why it’s critical that each ski area identifies its own climate risks and paths to action, and that we move forward with a strong, united voice for climate action.”

Riley points to NSAA’s awards for environmental effort as the shining examples. A-Basin, for example, was recognized for achieving 100% renewable electricity and carbon neutrality.

The big conglomerates like Vail and Alterra, according to Hartter, may be better positioned for impactful responses to climate change.

“A small resort may not have the resources to be able to do all of that,” he said of efforts like large-scale energy and water conservation projects. “So as an industry, it’s in looking at bigger scale changes and implementing those. We’re also able to make changes as an industry at scale, as opposed to sort of scattered onesie, twosies, different resorts doing their own thing.”

For Hartter, the ski industry needs to move beyond “table steaks” efforts like recycling and transportation initiatives.

“Cumulative impacts make it challenging for the ski industry going forward,” Hartter said. “That’s not to say it won’t survive, it just means that there are new and deeper challenges that will continue.”