“Well I’m California sober as they say / Lately I can find no other way / I can’t stay out and party like I did back in the day,” sings guitarist Billy Strings. He’s given up “the hard stuff and whiskey” and now the only thing coursing through his veins is good ol’ fashioned Mary Jane.

The song and the concept are called California sober: the idea that you can be considered drug free if the only substance you use is cannabis. (Booze, in moderation, sometimes gets a pass, too, depending on who you talk to.)

It’s a popular notion — and a divisive one among people in recovery.

As Boulder Weekly explored the proliferation of sober performing spaces, we asked the folks we talked to about their thoughts on “weed-only” sobriety. Here’s what they had to say.

Abstinence only

When Brooke Delgado was designing her study of sober musicians, she drew a hard line.

“I have had potential participants ask if California sober qualifies,” the CU Denver graduate student says. “And I say no. My study is on people living sober lifestyles, which is a lifestyle free of drugs and alcohol.

“You have to have some sort of criteria, and I was concerned [with] the conflict of someone in recovery versus someone who is California sober,” she says. “Can I compare the data?”

Some of Delgado’s study participants were California sober “for a period of time,” she says.

That tallies with the experiences of high-profile addicts like Demi Lovato, who also wrote her own “California Sober” song and once endorsed cannabis use before later stating that it led to her relapse. It’s the chief criticism of opponents of California sobriety, who argue that cannabis use is a slippery slope.

Steve-O, of Jackass fame, said of his choice to embrace abstinence-only sobriety, “My weed bone's connected to my booze bone. And my booze bone's connected to my coke bone.”

The chief criticism of opponents of California sobriety argue that cannabis use is a slippery slope, a sure way to trigger heavier drinking and drug use. Others say it’s a stepping stone on the recovery journey.

“If you’re going from being a really bad alcoholic, blacked out drunk, to being high, that’s a step in the right direction,” says Ryan Dart, a musician and songwriter who has been the manager for Colorado acts like Elephant Revival and Rose Hill Drive.

But for some people, “it really is a gateway” back to using. “There’s not one prescriptive answer for everybody,” Dart says. “Everybody’s at a different place in their life.”

Authentic and vulnerable

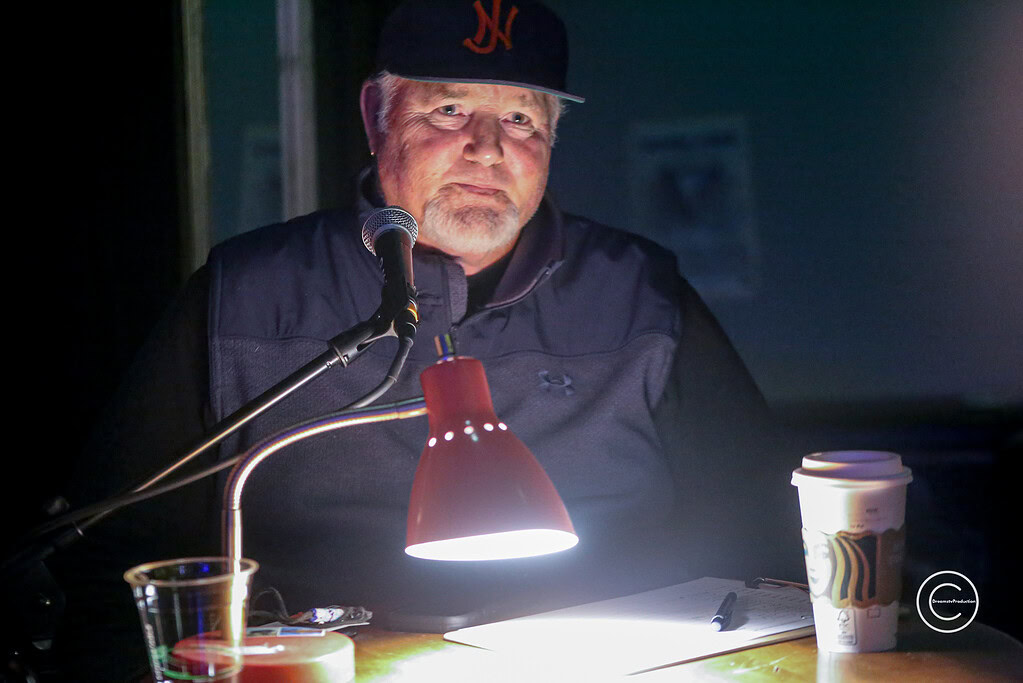

Joe Huisman, a former crack addict and founder of Second Chance Comedy, has worked with performers who, as he says, “smoke pot,” and he himself sometimes uses marijuana edibles to sleep.

“I don’t have any problem with that,” he says. “I don’t struggle with alcohol and marijuana like a lot of people do, so it’s a little easier for me than others. I do recognize that a lot of people in the audience cannot think about any type of substance.”

What substances people use is often less important than the work they’ve done to get and stay sober, Huisman says. Some of the early Second Chance performers were California sober, and they didn’t jive with the show’s vibe or mission.

“The goal is to try to bring stories that are relatable and bring humor to them so someone in the audience can laugh at their own pain or shame,” he says. These particular performers, “never really dealt with the underlying things that led to their addiction” and so weren’t able “to bring that authenticity and vulnerability that I’m looking for on the show.”

A new frontier

Challenging the dominance of so-called “sober-sober” apostles is the promise of psychedelics to treat addiction and the underlying trauma that pushes many people to use drugs and alcohol in the first place.

That’s how Paul Soderman came around to the concept of California sober — or, as he would prefer it to be known, Colorado sober. “We were the first to have legal weed,” he says.

After years of believing in and practicing “complete abstinence,” some of Soderman’s friends and confidants began disclosing their use of psychedelics: a rabbi who micro-doses shrooms for depression; other people in recovery “who have ayahuasca-ed themselves into amazing epiphanies.”

Psychedelics definitely have potential, Dart agrees, but he worries people are taking them as a form of escape rather than healing.

“Just because you’re doing something that’s a plant medicine, it doesn’t do the work for you,” he says. “Once you use that to rewire some pathways in your brain, you don’t need to keep going back to that well.”

When it comes to weed, Soderman is still skeptical, sharing the story of a promising young musician whose cannabis use killed his motivation and social life

“That is a mind-altering substance,” he says. “It’s always been controversial in our communities.”

At the end of the day, what Soderman counts as sober vs. addicted is “the fruit” — Whatever substance you’re using, does it get you closer to healing, or take you farther away from it?

For Huisman, the litmus test is one’s ability to live a functional, productive life free of destructive dependencies.

“Of all the drugs and substances,” he says, “if that’s the one you’re stuck on, more power to you. It’s not destroying lives like alcohol or hard drugs.”